Module 33: Lower Extremity I – Neurovasculature | Pelvis and Hip

Learning Objectives:

By the end of this class, students will be able to:

- Describe the pelvic bones and their features.

- Describe the features of the femur.

- Explain the anatomy of the hip joint.

- Describe the sciatic nerve, its branches, and the structures that its branches innervate.

- Describe the femoral and obturator nerves and the structures they innervate.

- Describe the arteries that supply the lower extremity.

- Explain venous return from the deep and superficial regions of the lower extremity.

Terms to Know

|

Bones of the Pelvis

Coxal (hip) joint

Proximal Femur

|

Nerves of the Lower Extremity

Vasculature of the Lower Extremity

Other Terms

*Covered only in lecture, not in this text |

Like the upper limb, the lower limb is divided into three regions.

- Thigh: portion of the lower limb located between the hip joint and knee joint

- Leg: specifically the region between the knee joint and the ankle joint

- Foot: distal to the ankle

Coxal Bone

This content will be covered in the assignment and briefly reviewed in lecture for this and the following modules.

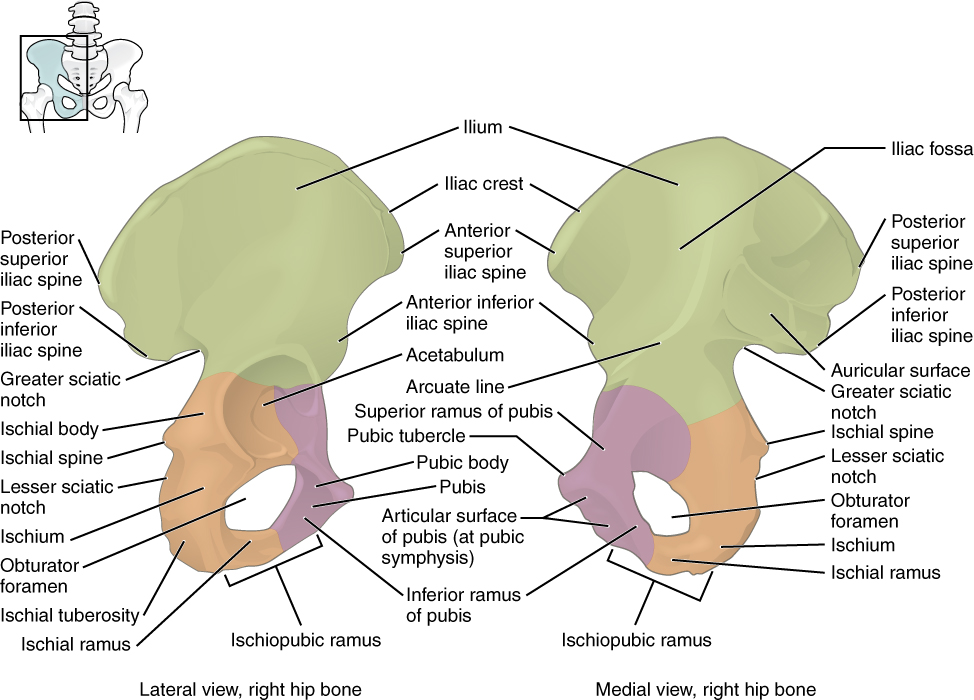

The paired coxal bones are the large, curved bones that form the lateral and anterior aspects of the pelvis. Each adult coxal bone is formed by three separate bones that fuse together during the late teenage years. These bony components are the ilium, ischium, and pubis. These names are retained and used to define the three regions of the adult coxal bone. The ilium is the fan-like, superior region that forms the largest part of the hip bone. It is firmly united to the sacrum at the largely immobile sacroiliac joint. The ischium forms the posteroinferior region of each hip bone. It supports the body when sitting. The pubis forms the anterior portion of the hip bone. The pubis curves medially, where it joins to the pubis of the opposite hip bone at a specialized joint called the pubic symphysis.

Ilium

When you place your hands on your waist, you can feel the arching, superior margin of the ilium along your waistline. This curved, superior margin of the ilium is the iliac crest. The rounded, anterior termination of the iliac crest is the anterior superior iliac spine. This bony landmark can be felt as the point at your anterolateral hip. Inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine is a rounded protuberance called the anterior inferior iliac spine. Posteriorly, the iliac crest curves downward to terminate as the posterior superior iliac spine. Muscles and ligaments surround but do not cover this bony landmark, so it sometimes appears as a depression or “dimple” located on the lower back. More inferiorly is the posterior inferior iliac spine. Both the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines serve as attachment points for the very strong ligaments that support the sacroiliac joint.

The winged upper portion of the ilium that flares upward and laterally is called the ala. The shallow depression located on the anteromedial (internal) surface of the upper ilium is called the iliac fossa. The inferior margin of this space is formed by the arcuate line of the ilium, the ridge formed by the pronounced change in curvature between the upper and lower portions of the ilium. The large, inverted U-shaped indentation located on the posterior margin of the lower ilium is called the greater sciatic notch.

Several of these bony markings serve as muscle attachments or landmarks that certain nerves or vessels travel through or near. We will cover the muscles and neurovasculature later in this or future modules. Here is an introduction connecting bony landmarks of the ilium with the muscles and neurovasculature:

- Iliac fossa: The origin for the iliacus muscle.

- Anterior superior iliac spine: Origin for the sartorius muscle.

- Anterior inferior iliac spine: Origin for the rectus femoris muscle.

- Greater sciatic notch: Becomes the greater sciatic foramen as the sacrospinal ligament closes the notch. The piriformis passes through it. The superior gluteal vessels and nerve pass above the piriformis in this foramen and the inferior gluteal vessels and nerves and sciatic nerve pass inferior to the piriformis.

Ischium

The ischium forms the posterolateral portion of the hip bone. The large, roughened area of the inferior ischium is the ischial tuberosity. This carries the weight of the body when sitting, and you can feel the ischial tuberosity as you shift your weight on the seat of a chair. Projecting superiorly and anteriorly from the ischial tuberosity is a narrow segment of bone called the ischial ramus. The slightly curved posterior margin of the ischium above the ischial tuberosity is the lesser sciatic notch. The bony projection separating the lesser sciatic notch and greater sciatic notch is the ischial spine.

Here is an introduction connecting bony landmarks of the ischium with the muscles and neurovasculature:

- Ischial tuberosity: Origin for the semimembranosus, semitendinosus, long head of biceps femoris, and hamstring part of the adductor magnus muscles.

- Lesser sciatic notch: Becomes the lesser sciatic foramen when the sacrotuberal ligament closes the notch. A lateral rotator (which we don’t ask you to know) travels through it along with several smaller vessels and nerves.

Pubis (Pubic Bone)

The pubis forms the anterior portion of the os coxae. The small bump located at the anterior aspect of the pubis is called the pubic tubercle. The superior ramus (plural rami) is the segment of bone that passes laterally from the body of the pubis to join the ilium. The narrow ridge running along the superior margin of the superior pubic ramus is the pectineal line of the pubis. Extending downward and laterally from the body of the pubis is the inferior pubic ramus. The inferior pubic ramus extends downward to join the ischial ramus. Together, these form the single ischiopubic ramus, which extends from the pubic body to the ischial tuberosity. The hole that appears posterior to the pubis, formed by the pubis and ischium together, is called the obturator foramen. This space is largely filled in by a layer of connective tissue.

The right and left pubic bones meet at the pubic symphysis. The pubic arch is the bony structure formed by the pubic symphysis, and the inferior pubic rami of the adjacent pubic bones. The inverted V-shape formed as the ischiopubic rami from both sides come together at the pubic symphysis is called the subpubic angle.

Here is an introduction connecting bony landmarks of the ischium with the muscles and neurovasculature:

- Obturator foramen: The obturator nerve, artery, and vein travel through this foramen.

- Pectineal line: Origin for the pectineus muscle.

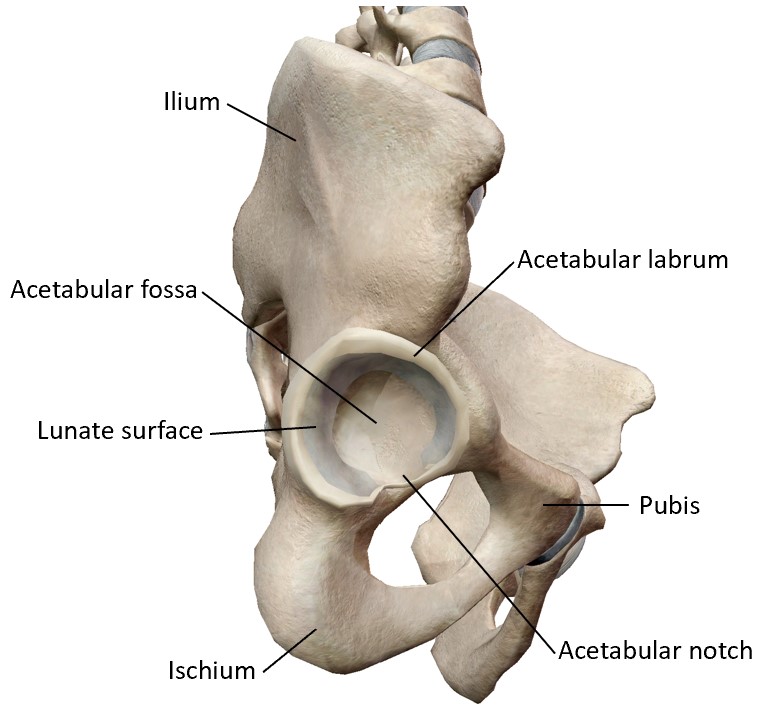

The ilium, pubis, and ischium converge centrally to form a deep, cup-shaped cavity called the acetabulum. This is located on the lateral side of the os coxae and is part of the hip joint.

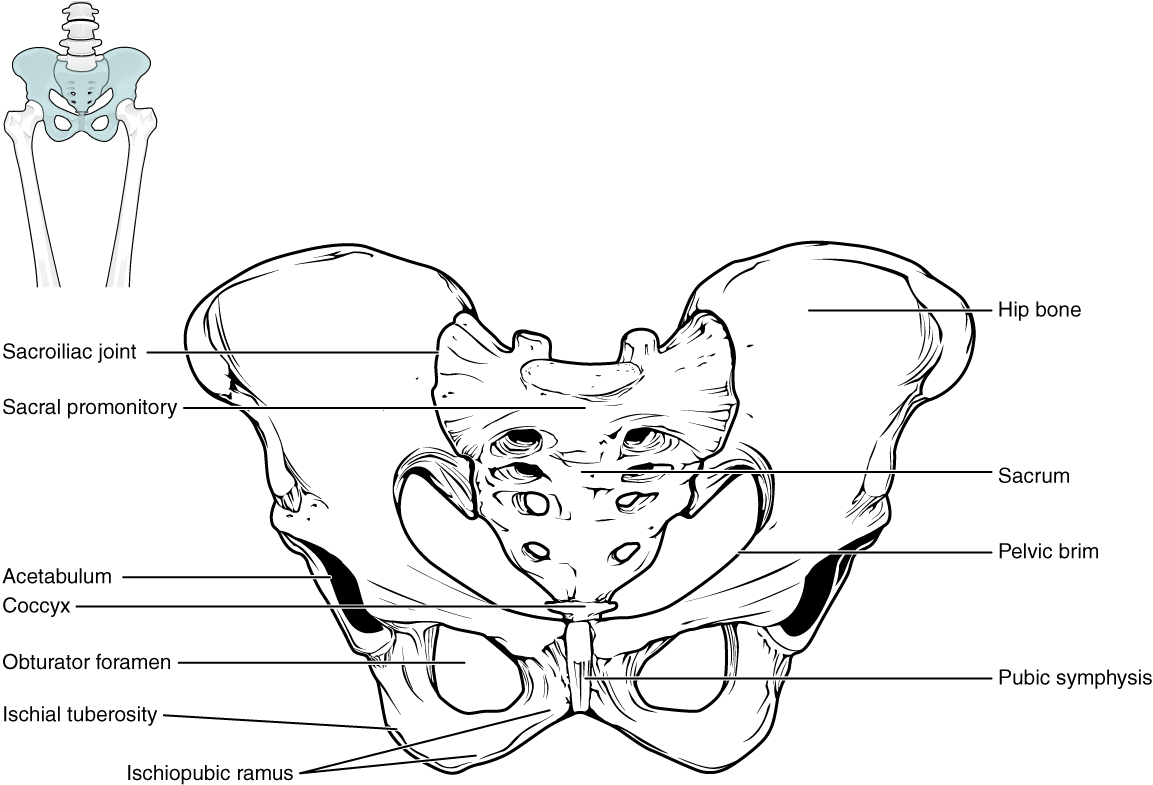

The Pelvis

This content will be covered in the assignment and briefly reviewed in lecture.

The pelvic girdle is formed by the right and left os coxae as well as the sacrum and coccyx of the vertebral column. The sacrum is part of the axial skeleton, while the os coxae are part of the appendicular skeleton. Each os coxae is firmly joined to the axial skeleton at the sacroiliac joint, between the sacrum and the ilium of the os coxae. This connection between the appendicular skeleton and axial skeleton is much larger than that of the upper extremity, providing more stability at this joint. This stability is important because we are transferring our body weight through the sacroiliac joint. Though there is little mobility at the joint, only gliding motions, the immobility compared to the upper extremity provides a strong foundation for the torso and upper body as it rests on top of the mobile lower limbs. The sacroiliac joint is supported by strong ligaments that are attached between the sacrum and ilium.

The right and left pubic bones also converge anteriorly to form a joint at the pubic symphysis. There is a fibrocartilaginous disc at the pubic symphysis at this joint.

The pelvis has several important functions. Its primary role is to support the weight of the upper body when sitting and to transfer this weight to the lower limbs when standing. It serves as an attachment point for trunk and lower limb muscles, and also protects the internal pelvic organs.

When standing in the anatomical position, the pelvis is tilted anteriorly. In this position, the anterior superior iliac spines and the pubic tubercles lie in the same vertical plane, and the anterior (internal) surface of the sacrum faces forward and downward.

The space enclosed by the bony pelvis is divided into two regions. The broad, superior region, defined laterally by the ala of the ilium, is called the greater pelvis (greater pelvic cavity). This broad area is occupied by portions of the small and large intestines. More inferiorly, the narrow, rounded space of the lesser pelvis (lesser pelvic cavity) contains the bladder and other pelvic organs. The pelvic inlet (also known as the pelvic brim) forms the superior margin of the lesser pelvis, separating it from the greater pelvis. It is defined by a line formed by the upper margin of the pubic symphysis anteriorly, and the pectineal line of the pubis, the arcuate line of the ilium, and the anterior margin of the superior sacrum posteriorly. The inferior limit of the lesser pelvic cavity is called the pelvic outlet. This large opening is defined by the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis anteriorly, and the ischiopubic ramus, the ischial tuberosity, and the inferior tip of the coccyx posteriorly. Because of the anterior tilt of the pelvis, the lesser pelvis is also angled, giving it an anterosuperior (pelvic inlet) to posteroinferior (pelvic outlet) orientation.

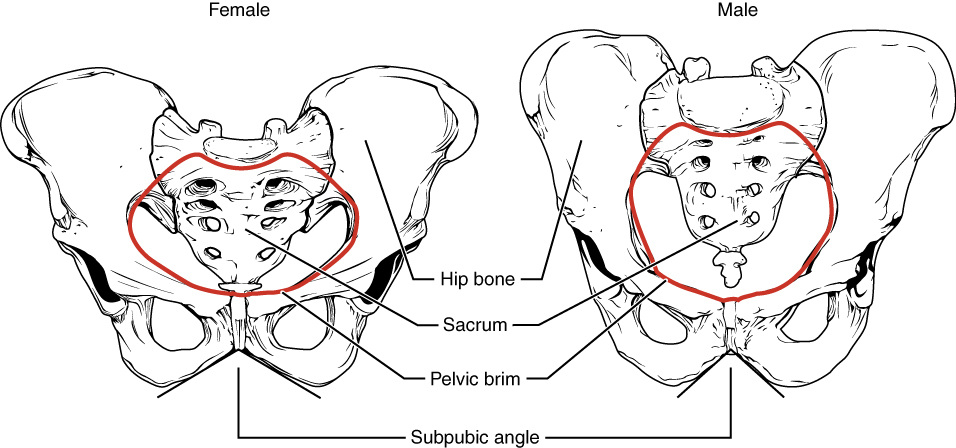

Comparison of the Female and Male Pelvis

The differences between the adult female and male pelvis relate to function and body size. In general, the bones of the male pelvis are thicker and heavier, adapted for support of the male’s heavier physical build. The greater sciatic notch of the male hip bone is narrower and deeper than the broader notch of females. Because the female pelvis is adapted for childbirth, it is wider than the male pelvis, as evidenced by the distance between the anterior superior iliac spines. The ischial tuberosities of females are also farther apart, which increases the size of the pelvic outlet. Because of this increased pelvic width, the subpubic angle is larger in females (greater than 80 degrees) than it is in males (less than 70 degrees). The female sacrum is wider, shorter, and less curved, and the anterior margin of the superior sacrum (called the sacral promontory) projects less into the pelvic cavity, thus giving the female pelvic inlet (pelvic brim) a more rounded or oval shape compared to males. The lesser pelvic cavity of females is also wider and more shallow than the narrower, deeper, and tapering lesser pelvic cavity of males. Because of the obvious differences between female and male os coxae, this is the one bone of the body that allows for the most accurate sex determination.

| Overview of Differences between the Female and Male Pelvis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Female pelvis | Male pelvis | |

| Pelvic weight | Bones of the pelvis are lighter and thinner | Bones of the pelvis are thicker and heavier |

| Pelvic inlet shape | Pelvic inlet has a round or oval shape | Pelvic inlet is heart-shaped |

| Lesser pelvic cavity shape | Lesser pelvic cavity is shorter and wider | Lesser pelvic cavity is longer and narrower |

| Subpubic angle | Subpubic angle is greater than 80 degrees | Subpubic angle is less than 70 degrees |

| Pelvic outlet shape | Pelvic outlet is rounded and larger | Pelvic outlet is smaller |

Femur

This content will be covered in the assignment and briefly reviewed in lecture for this and the following modules.

This section will cover the features of the proximal femur. The next module will cover the features of the distal femur.

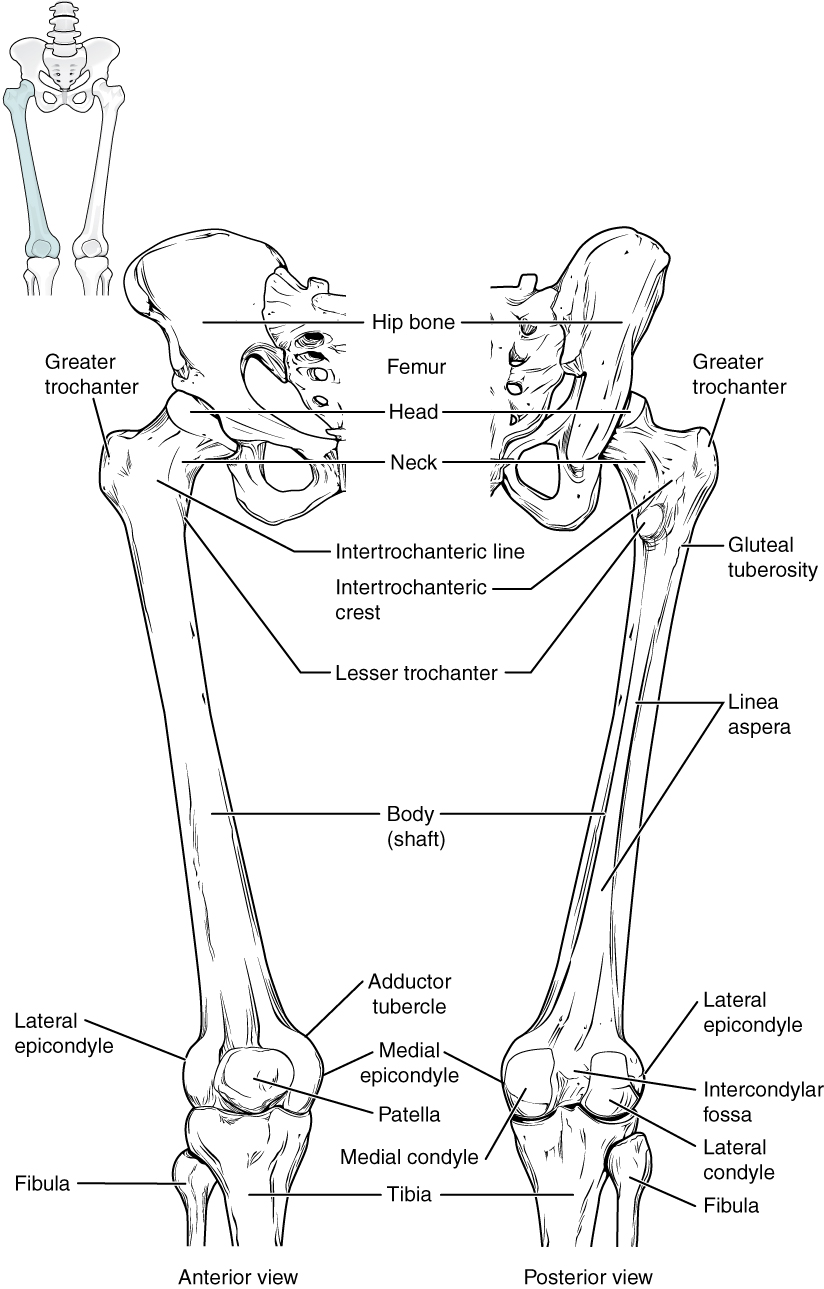

The femur is the single bone of the thigh region. It is the longest and strongest bone of the body, and accounts for approximately one-quarter of a person’s total height. The rounded, proximal end is the head of the femur, which articulates with the acetabulum of the os coxae to form the hip joint. The fovea, or fovea capitis, is a minor indentation on the medial side of the femoral head that serves as the site of attachment for the ligament of the head of the femur.

The narrowed region below the head is the neck of the femur. The greater trochanter is the large, upward, bony projection located above the base of the neck. It can be felt just under the skin on the lateral side of your upper thigh. The lesser trochanter is a small, bony prominence that lies on the medial aspect of the femur, just below the neck. Running between the greater and lesser trochanters on the anterior side of the femur is the roughened intertrochanteric line.

The elongated shaft of the femur has a slight anterior bowing or curvature. At its proximal end, the posterior shaft has the gluteal tuberosity, a roughened area extending inferiorly from the greater trochanter. More inferiorly, the gluteal tuberosity becomes continuous with the linea aspera, a roughened ridge that passes distally along the posterior side of the mid-femur. Multiple muscles of the hip and thigh regions make long, thin attachments to the femur along the linea aspera.

Here is an introduction connecting bony landmarks of the proximal femur with their associated muscles, ligaments, and joints:

- Head: Articulates with the acetabulum of the os coxae to form the hip, or coxal, joint.

- Fovea capitis: Attachment site for the ligament of the head of the femur, or ligamentum teres.

- Greater trochanter: Insertion for the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus. Origin for the vastus lateralis.

- Lesser trochanter: Insertion for the psoas major and iliacus, which together insert at this point as the iliopsoas.

- Gluteal tuberosity: Insertion for the gluteus maximus.

- Linea aspera: Origin for the vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and short head of biceps femoris. Insertion for the adductor longus, adductor brevis, and hamstring part of adductor magnus.

Coxal (Hip) Joint

This content will be covered in the assignment and briefly reviewed in lecture.

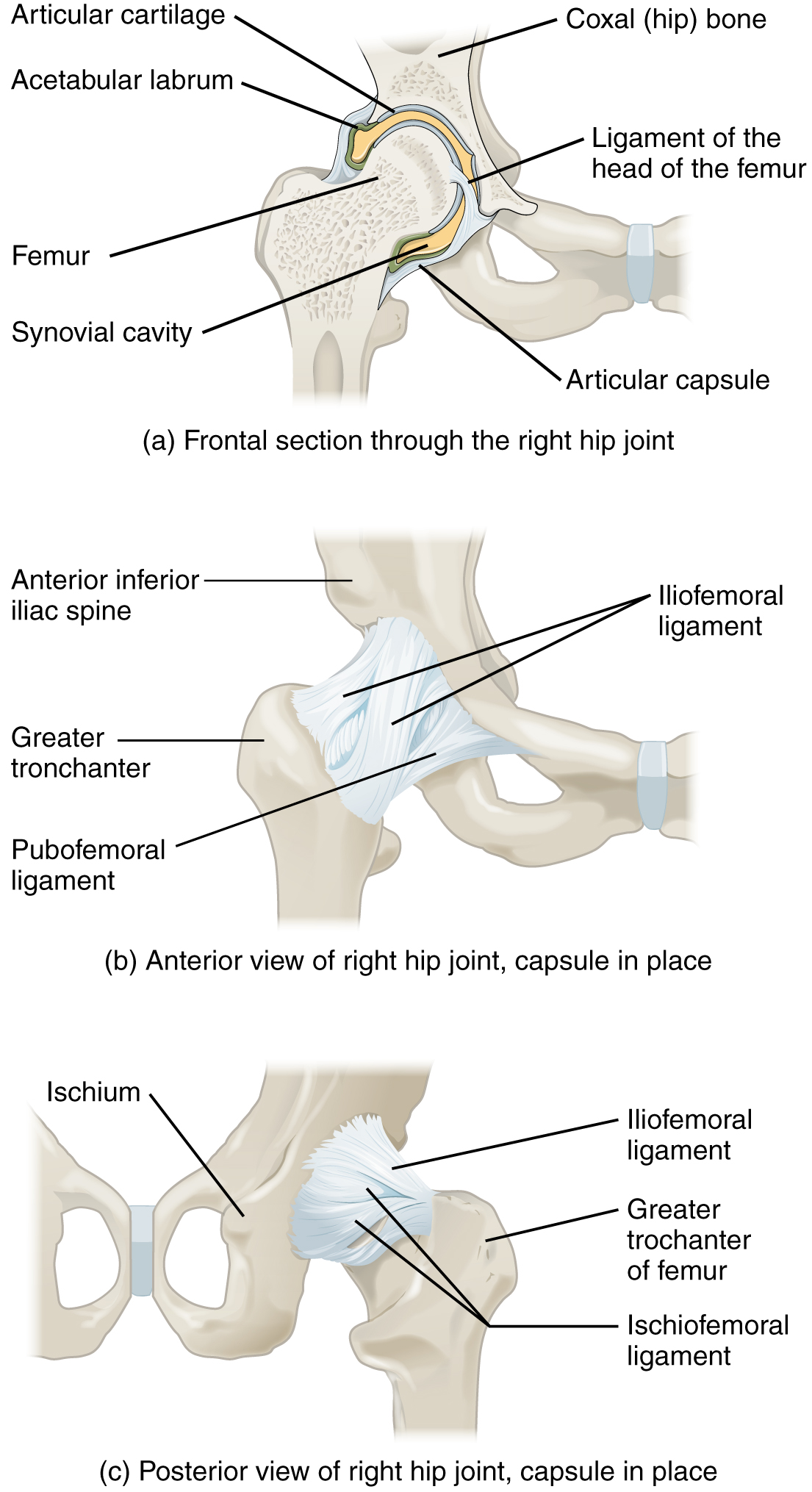

The coxal joint, or hip joint, is a multiaxial ball-and-socket joint between the head of the femur and the acetabulum of the os coxae. The hip carries the weight of the body and thus requires strength and stability during standing and walking. As a result, its range of motion is more limited than at the shoulder joint.

The acetabulum, is the socket portion of the coxal joint. This space is deep and has a large articulation area for the femoral head, thus giving stability and weight bearing ability to the joint. The acetabular fossa is the rougher region at the center of the acetabulum. The lunate surface is the smooth, curved portion of the acetabulum that is the primary source of contact of the femoral head on the acetabulum. The acetabulum is further deepened by the acetabular labrum, a fibrocartilage lip attached to the outer margin of the acetabulum that increases the stability of the joint. Inferiorly, the acetabular notch is the region that appears as a gap in the lunate surface and acetabular labrum. This space allows neurovasculature to enter the joint space.

The surrounding articular capsule is strong, with several thickened areas forming intrinsic ligaments. These ligaments arise from the bones of the os coxae, at the margins of the acetabulum, and attach to the femur at the base of the neck. The ligaments are the iliofemoral ligament, pubofemoral ligament, and ischiofemoral ligament, all of which spiral around the head and neck of the femur. The ligaments are tightened by extension at the hip, thus pulling the head of the femur tightly into the acetabulum when in the upright, standing position. Very little additional extension of the thigh is permitted beyond this vertical position. These ligaments thus stabilize the hip joint and allow you to maintain an upright standing position with only minimal muscle contraction to support the joint. Inside of the articular capsule, the ligament of the head of the femur (ligamentum teres) spans between the acetabulum and femoral head. This intracapsular ligament is normally slack and does not provide any significant joint support, but it does provide a pathway for an important artery that supplies the head of the femur (artery to the head of the femur).

Vasculature of the Lower Limbs

This content will be covered in lecture.

Arteries Serving the Lower Limbs

Internal Iliac Artery and Branches

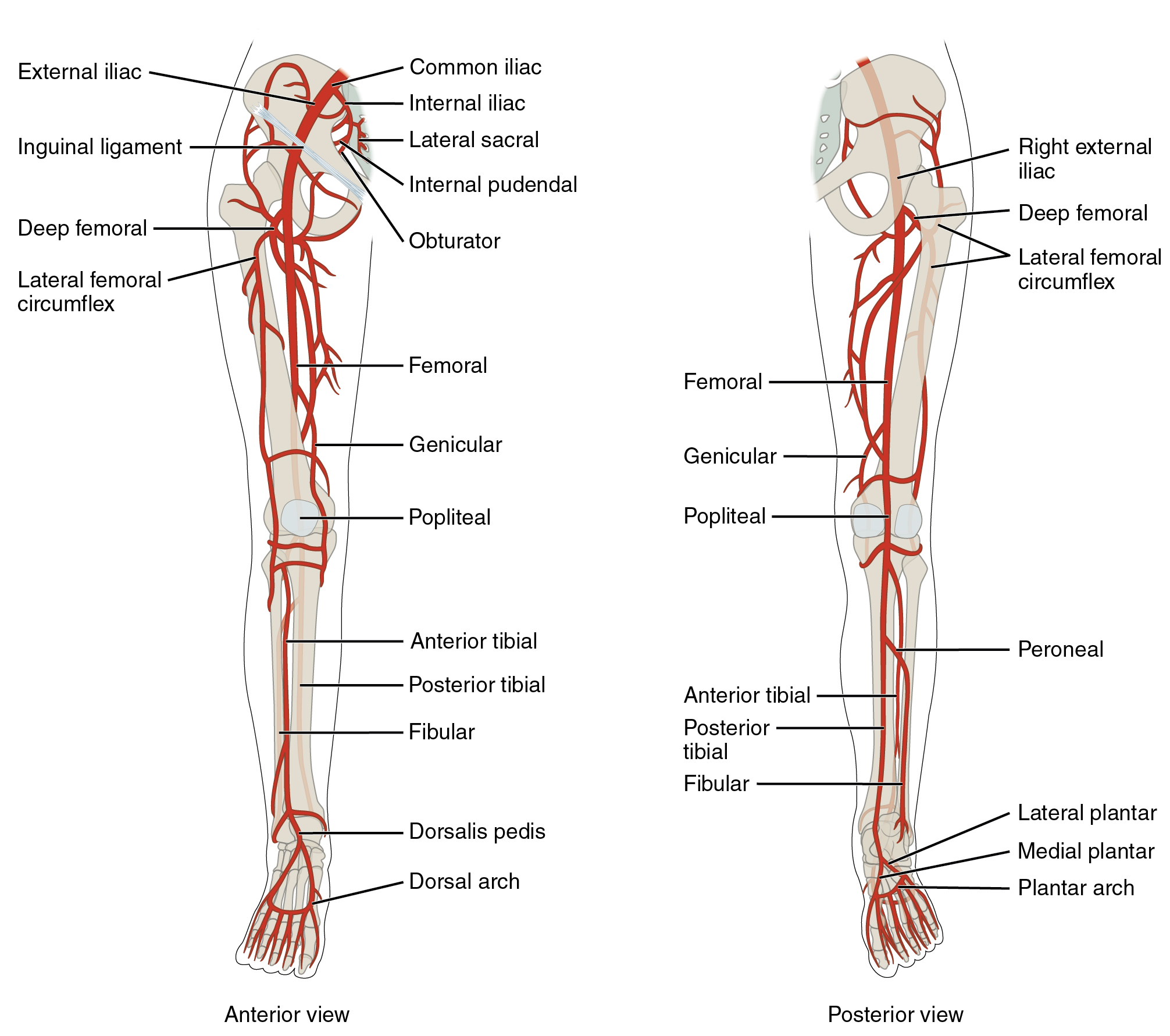

The internal iliac artery primarily supplies muscles and organs in the pelvic region. However, it gives off a few branches that supply muscles of the lower extremity.

- Superior and inferior gluteal arteries: These anastomose with each other and together supply the gluteal muscles.

- Obturator artery: Supplies the muscles of the superior medial thigh (adductors) and the skin of the medial thigh.

- Artery to the femoral head: Branches from the obturator artery supply the femoral head. It is the primary supply to the femoral head in children, though other arteries also provide a larger portion of blood to this structure in adults.

External Iliac Artery and Branches

The external iliac artery branches from the common iliac artery in the pelvis to supply the majority of the lower extremity. It exits the body cavity and enters the femoral triangle as the femoral artery which it becomes as it passes through the body wall. The femoral triangle is the region of the anterior thigh bounded by the inguinal ligament superiorly, sartorius laterally, and adductor longus medially.

The femoral artery gives off several smaller branches that supply blood to muscles of the thigh:

-

Deep femoral (profunda femoris) artery: Deep muscles of the thigh.

-

Medial circumflex femoral artery: Hip joint and a few medial thigh muscles.

-

Lateral circumflex femoral artery: Quadriceps, hip and knee joints.

-

The femoral artery also gives rise to branches that provide blood to the knee region. As the femoral artery passes posterior to the knee and enters the popliteal fossa, the space posterior to the knee joint, it becomes the popliteal artery.

The popliteal artery branches into the arteries that supply the leg and eventually the foot:

- Anterior tibial artery: Supplies blood to the anterior compartment of the leg.

- Dorsalis pedis artery: The anterior tibial artery becomes this artery as it crosses the ankle region and enters the dorsal aspect of the foot. It supplies the muscles and skin of the dorsal foot.

- Posterior tibial artery: Supplies both the deep and superficial posterior compartments of the leg.

- Medial & lateral plantar arteries: These arteries branch from the posterior tibial artery after it wraps around the medial malleolus and it enters the plantar aspect of the foot. They supply the medial and lateral portions of the plantar aspect of the foot.

- Fibular (peroneal) artery: This artery is a branch off of the posterior tibial artery in the superior leg, shortly after the branching of the popliteal artery. It supplies the lateral compartment of the leg.

- Plantar arch: Formed by anastomosis of the medial and lateral plantar arteries and supplies the plantar aspect of the foot.

- Digital arteries: Branches off of the plantar arch that supply the toes.

Veins Draining the Lower Limbs

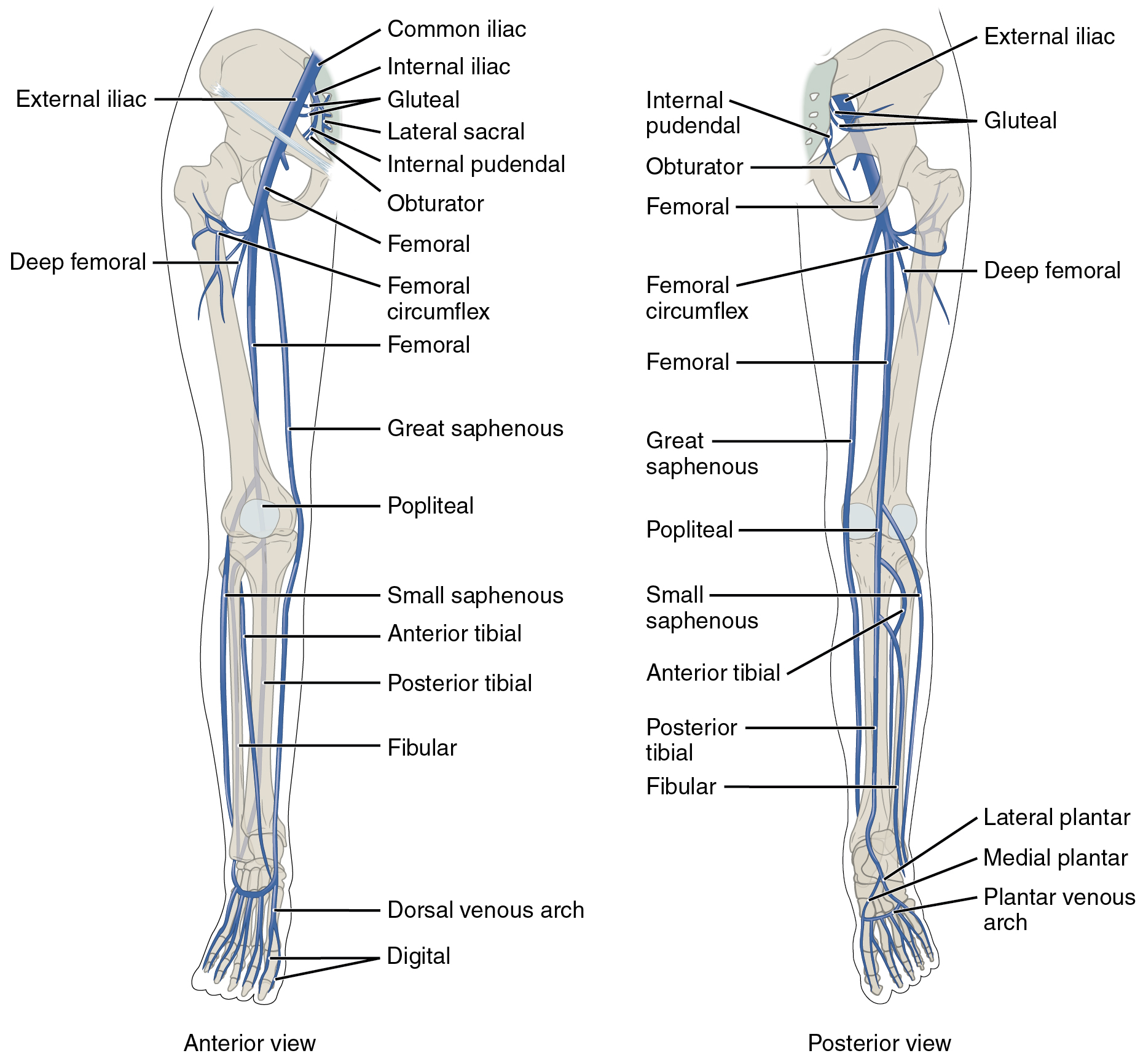

The deep veins of the lower extremity travel with and drain the same areas supplied by the artery of the same name. The anterior tibial vein combines with the posterior tibial vein and the fibular vein to form the popliteal vein.

The small saphenous vein is located on the lateral surface of the leg and drains blood from the superficial regions of the lower leg and foot. It flows into to the popliteal vein. As the popliteal vein passes behind the knee in the popliteal region, it becomes the femoral vein.

The great saphenous vein is a prominent surface vessel located on the medial surface of the leg and thigh that collects blood from the superficial portions of these areas. It drains into the femoral vein in the femoral triangle. The femoral vein becomes the external iliac vein when it enters the pelvic cavity.

Nerves of the Lower Extremity

This content will be covered in lecture.

Nerves of the lower extremity are formed from two plexuses:

- Lumbar plexus: Anterior rami of spinal nerves L1-L4

- Sacral plexus: Anterior rami of spinal nerves L4-S4

Two branches emerge from the lumbar plexus:

- Obturator nerve: Innervates all adductor muscles (though the pectineus also receives innervation from the femoral nerve and the hamstring portion of adductor magnus is innervated by the tibial division of the sciatic nerve).

- Femoral nerve: Formed from anterior rami of L2-L4, it innervates the anterior thigh muscles (though pectineus is also innervated by the obturator nerve) and skin of the anterior thigh and medial leg.

Three branches emerge from the sacral plexus:

- Superior gluteal nerve: Innervates gluteus medius and gluteus minimus

- Inferior gluteal nerve: Innervates gluteus maximus

- Sciatic nerve: This nerve is actually two nerves, the common fibular (peroneal) and tibial nerves wrapped together in a common sheath. As a result, the sciatic nerve itself doesn’t innervate any muscles, but its two branches do. The branches typically split from each other in the superior portion of the popliteal fossa, but they can separate as far superiorly as the gluteal region.

- Tibial nerve: In the thigh, the tibial nerve innervates the majority of the posterior compartment muscles (long head of biceps femoris, semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and the hamstring portion of adductor magnus). It continues into the leg to supply both the superficial and deep posterior compartments.

- Medial & lateral plantar nerves: After wrapping around the medial malleolus, the tibial nerve branches into the medial and lateral plantar nerves, which supply the muscles of the plantar aspect of the foot.

- Common fibular (peroneal) nerve: The common fibular nerve only innervates one portion of one muscle in the thigh, the short head of biceps femoris. It continues inferiorly into the leg and branches into the:

- Deep fibular (peroneal) nerve: Supplies the muscles of the anterior compartment of the leg and dorsal foot.

- Superficial fibular (peroneal) nerve: Supplies the muscles of the lateral compartment of the leg.

- Tibial nerve: In the thigh, the tibial nerve innervates the majority of the posterior compartment muscles (long head of biceps femoris, semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and the hamstring portion of adductor magnus). It continues into the leg to supply both the superficial and deep posterior compartments.