Module 34: Lower Extremity II – Gluteal Region, Thigh, and Knee

Learning Objectives:

By the end of this class, students will be able to:

- Describe the features of the femur.

- Name the origins, insertions, innervation, and blood supply of the gluteal and thigh muscles.

- Understand the function of thigh muscles that act on the hip and knee.

- Describe the bones of the knee joint and leg and their features.

- Explain the anatomy of the knee joint.

Terms to Know

|

Bones of the Lower Extremity

Knee Joint

Other Terms

|

Muscles of the Gluteal Region

Muscles of the Thigh

*Covered only in lecture, not in this text |

The Femur

This content will be covered in the assignment and briefly reviewed in lecture.

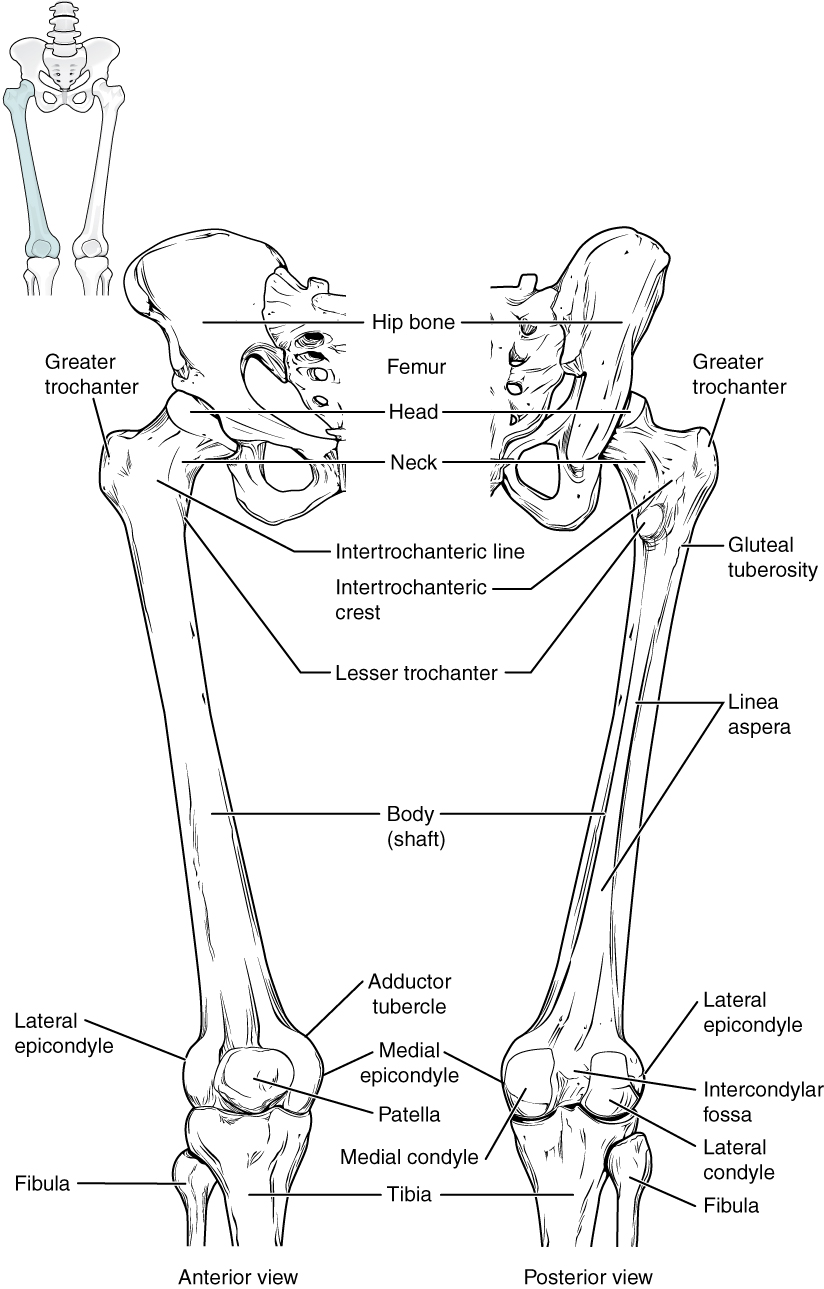

You covered the features of the proximal femur in the previous module. This section will cover the features of the distal femur.

The distal end of the femur has medial and lateral bony expansions. On the lateral side, the smooth portion that covers the distal and posterior aspects of the lateral expansion is the lateral femoral condyle of the femur. The roughened area on the outer, lateral side of the condyle is the lateral femoral epicondyle of the femur. Similarly, the smooth region of the distal and posterior medial femur is the medial femoral condyle, and the irregular outer, medial side of this is the medial femoral epicondyle of the femur. The lateral and medial condyles articulate with the tibia to form the knee joint, and the medial condyle is slightly larger than the lateral condyle. The epicondyles provide attachment for muscles and supporting ligaments of the knee. Extending superiorly from the medial and lateral condyles are the medial and lateral supracondylar ridges, which also serve as muscle attachment sites.

The adductor tubercle is a small bump located at the superior margin of the medial epicondyle. Posteriorly, the medial and lateral condyles are separated by a deep depression called the intercondylar fossa. Anteriorly, the smooth surfaces of the condyles join together to form a wide groove called the patellar surface, which provides for articulation with the patella bone.

Here is an introduction connecting bony landmarks of the distal femur with the muscles and neurovasculature:

- Medial and lateral condyles: Articular surfaces for articulation with the medial and lateral condyles of the tibia

- Medial epicondyle: Attachment site for the medial collateral ligament, origin for the medial head of the gastrocnemius

- Lateral epicondyle: Attachment site for the lateral collateral ligament, origin for the lateral head of the gastrocnemius

- Intercondylar fossa: Attachment site for the cruciate ligaments of the knee

- Patellar surface: Articular surface for articulation with the patella

- Adductor tubercle: Insertion for part of the adductor magnus

Patella

This content will be covered in the assignment and briefly reviewed in lecture.

The patella (kneecap) is largest sesamoid bone of the body. A sesamoid bone is a bone that is incorporated into the tendon of a muscle where that tendon crosses a joint. The sesamoid bone articulates with the underlying bones to protect the underlying structures of the knee joint and increase the mechanical efficiency of the muscle. The patella is found in the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle. The patella has medial and lateral articular facets that articulate with the medial and lateral portions of the patellar surface of the femur. The patella lifts the tendon away from the knee joint, which increases the leverage power of the quadriceps femoris muscle as it acts across the knee. The patella does not articulate with the tibia.

Tibia

This content will be covered in the assignment and briefly reviewed in lecture.

This section will cover the features of the proximal tibia. The distal tibia will be covered in the next module.

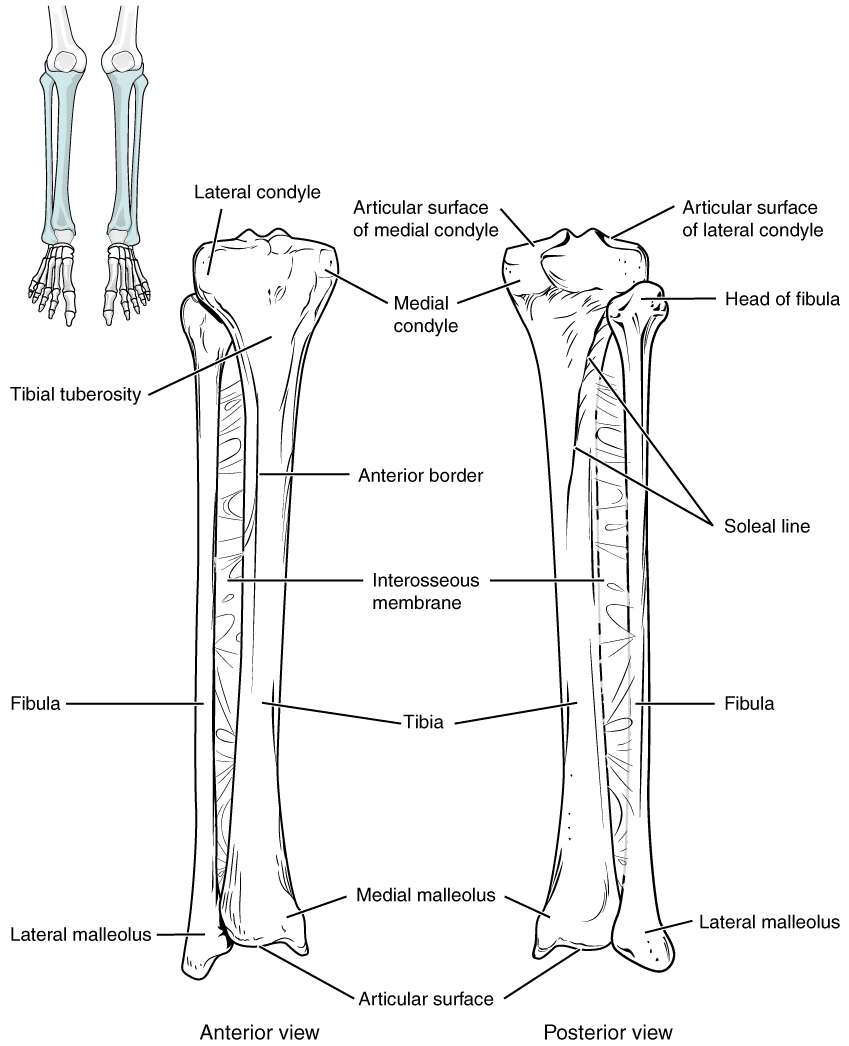

The tibia is the medial bone of the leg and is larger than the fibula, with which it is paired. The tibia is the main weight-bearing bone of the lower leg and the second longest bone of the body, after the femur.

The proximal end of the tibia is greatly expanded. The two sides of this expansion form the medial condyle of the tibia and the lateral condyle of the tibia. The tibia does not have epicondyles. The top surface of each condyle is smooth and flattened. These areas articulate with the medial and lateral condyles of the femur to form the knee joint.

The tibial tuberosity is an elevated area on the anterior side of the tibia, near its proximal end. It is the final site of attachment for the muscle tendon associated with the patella. Just lateral to the tibial tuberosity is Gerdy’s tubercle, the insertion for the iliotibial tract (IT band). Just medial to the tibial tuberosity is the pes anserine insertion, which is the insertion point for three muscles of the thigh.

Here is an introduction connecting bony landmarks of the proximal tibia with the muscles and neurovasculature:

- Medial and lateral condyles: Articular surfaces for articulation with the medial and lateral condyles of the femur

- Tibial tuberosity: Insertion for the quadriceps muscle group and patellar tendon/ligament

- Gerdy’s tubercle: Insertion for the iliotibial tract (IT Band)

- Pes anserine insertion: Insertion for the semitendinosus, sartorius, and gracilis

Fibula

This content will be covered in the assignment and briefly reviewed in lecture.

This section will cover the features of the proximal fibula. The distal fibula will be covered in the next module.

The fibula is the slender bone located on the lateral side of the leg. The fibula bears little, if any weight (around 0%-12% of body weight depending on the individual). It serves primarily for muscle attachments and thus is largely surrounded by muscles.

The head of the fibula is the small, knob-like, proximal end of the fibula. It articulates with the inferior aspect of the lateral tibial condyle, forming the proximal tibiofibular joint. The fibular head is an insertion point for the biceps femoris muscle and the distal attachment site for the lateral collateral ligament.

Knee Joint

This content will be covered in lecture.

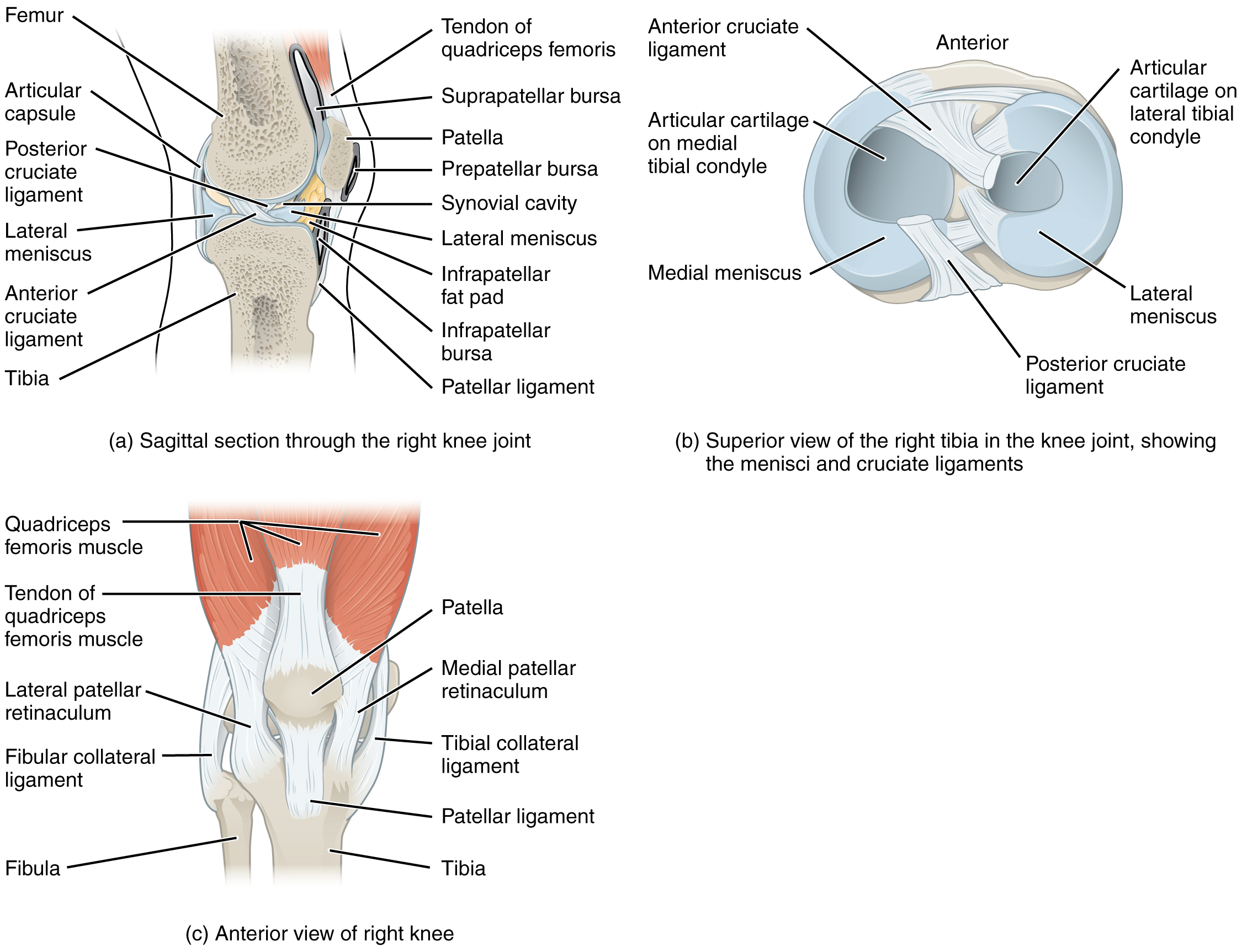

The knee joint, or tibiofemoral joint, is located between the medial and lateral condyles of the femur and the medial and lateral condyles of the tibia. It also involves the patellofemoral joint between the patella and the patellar surface of the femur. These joints are enclosed within a single articular capsule. The knee functions as a hinge joint, allowing flexion and extension of the leg. This action is generated by both rolling and gliding motions of the femur on the tibia. In addition, some rotation of the tibia on the femur occurs, though it is minimal and, in part, related to the size difference between the femoral condyles.

At the patellofemoral joint, the patella slides vertically within a groove on the distal femur. The patella is a sesamoid bone incorporated into the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle. Given that the patella is a sesamoid bone within the tendon, some anatomists call the structure connecting the patella to the tibial tuberosity the patellar tendon. Other anatomists consider this to be the patellar ligament because it connects bone to bone (patella to tibial tuberosity). We consider either acceptable in this course.

The condyles of the femur are rounded, and the tibial condyles are relatively flat. The superior surface of the tibial condyles are often referred to as the tibial plateau. During flexion and extension, the condyles of the femur both roll and glide over the tibial plateau. The rolling action produces flexion or extension, while the gliding action serves to maintain the femoral condyles centered over the tibial condyles, thus ensuring maximal bony, weight-bearing support for the femur in all knee positions. As the knee comes into full extension, the femur undergoes a slight medial rotation in relation to tibia. The rotation results because the lateral condyle of the femur is slightly smaller than the medial condyle. Thus, the lateral condyle finishes its rolling motion first, followed by the medial condyle. The resulting small medial rotation of the femur serves to “lock” the knee into its fully extended and most stable position. Flexion of the knee is initiated by a slight lateral rotation of the femur on the tibia, which “unlocks” the knee. This lateral rotation motion is produced by the popliteus muscle of the deep posterior compartment of the leg.

Located between the articulating surfaces of the femur and tibia are two articular discs, the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus. Each is a C-shaped fibrocartilage structure that is thin along its inside margin and thick along the outer margin. They are attached to their tibial condyles, but do not attach to the femur. The medial meniscus is anchored at its outer margin to the articular capsule and medial collateral ligament. The menisci provide padding and cushion between the bones and help to fill the gap between the round femoral condyles and flattened tibial condyles.

The knee joint has multiple ligaments that provide support. The lateral collateral ligament (fibular collateral ligament) is on the lateral side and spans from the lateral epicondyle of the femur to the head of the fibula. The medial collateral ligament (tibial collateral ligament) is on the medial aspect of the knee and runs from the medial epicondyle of the femur to the medial tibia. As it crosses the knee, the medial collateral ligament is firmly attached on its deep side to the articular capsule and to the medial meniscus, an important factor when considering knee injuries. In the fully extended knee position, both collateral ligaments are taut (tight), thus serving to stabilize and support the extended knee and preventing side-to-side or rotational motions between the femur and tibia.

Inside the knee are two intracapsular ligaments, the anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament. These ligaments are anchored inferiorly to the tibia at the intercondylar eminence, the roughened area between the tibial condyles. The cruciate ligaments are named for whether they are attached anteriorly or posteriorly to this tibial region. Each ligament runs diagonally upward to attach to the inner aspect of a femoral condyle. The cruciate ligaments are named for the X-shape formed as they pass each other (cruciate means “cross”). The posterior cruciate ligament is the stronger ligament. It prevents the tibia from moving posteriorly on the femur (or the femur from moving anteriorly on the tibia). The anterior cruciate ligament prevents the tibia from moving anteriorly on the femur (or the femur from moving posteriorly on the tibia). The anterior cruciate ligament also becomes tight when the knee is extended, and thus resists hyperextension. Because these ligaments cross each other, they also provide rotational stability, preventing excessive rotation between the femur and tibia.

Muscles of the Gluteal Region and Thigh

This content will be covered in the assignment and reviewed in lecture.

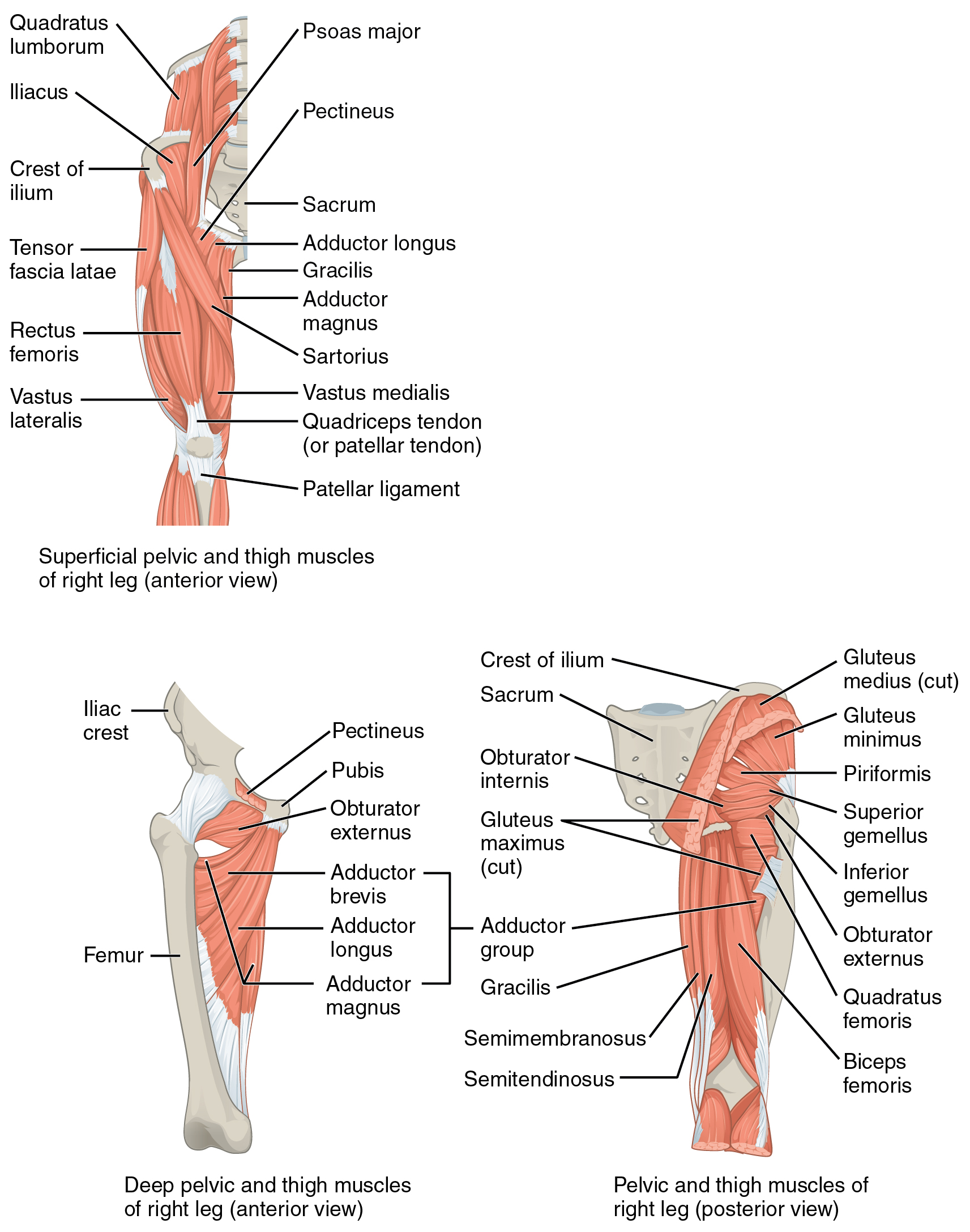

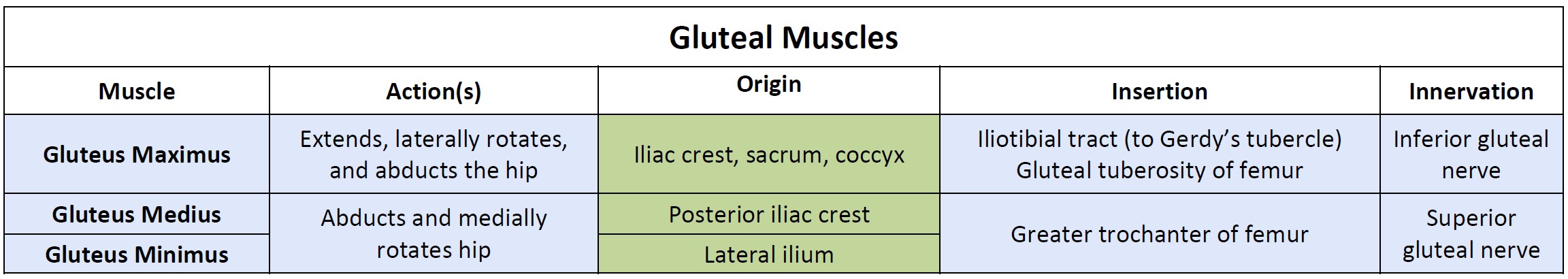

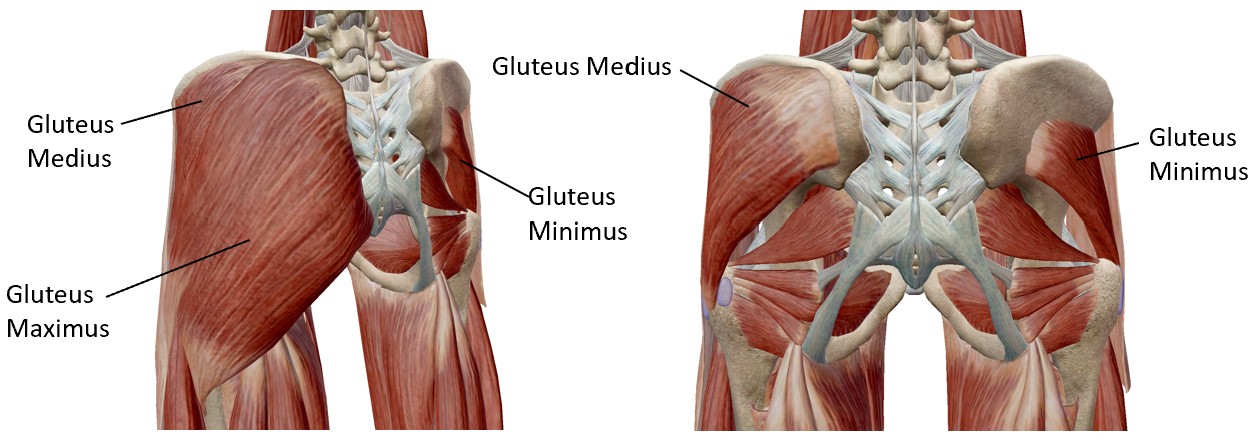

The gluteus maximus is the largest and most superficial; deep to the gluteus maximus is the gluteus medius, and deep to the gluteus medius is the gluteus minimus, the smallest and deepest of the trio.

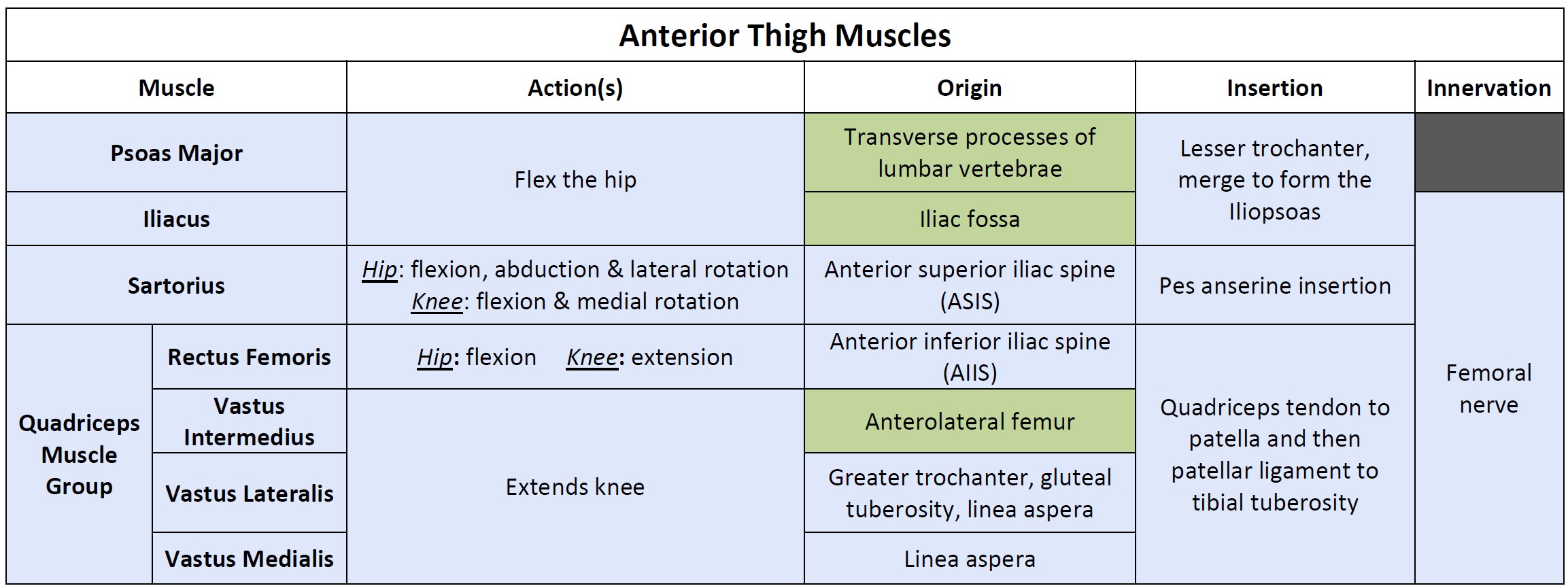

In the anterior thigh, the quadriceps femoris group is composed of four muscles that extend and stabilize the knee. The rectus femoris is the most superficial of these muscles and is located centrally on the lateral aspect of the thigh. The vastus lateralis and vastus medialis are located laterally and medially on the anterior thigh, while the vastus intermedius is between them, deep to the rectus femoris. They merge to form the quadriceps tendon. The sartorius is a band-like muscle that extends from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pes anserine insertion on the medial aspect of the proximal tibia. This versatile muscle flexes the leg at the knee and flexes, abducts, and laterally rotates the leg at the hip, allowing us to sit cross-legged. Two hip flexors cross from the pelvis into the anterior thigh to insert at the lesser trochanter. The psoas major and iliacus muscles merge to form the iliopsoas.

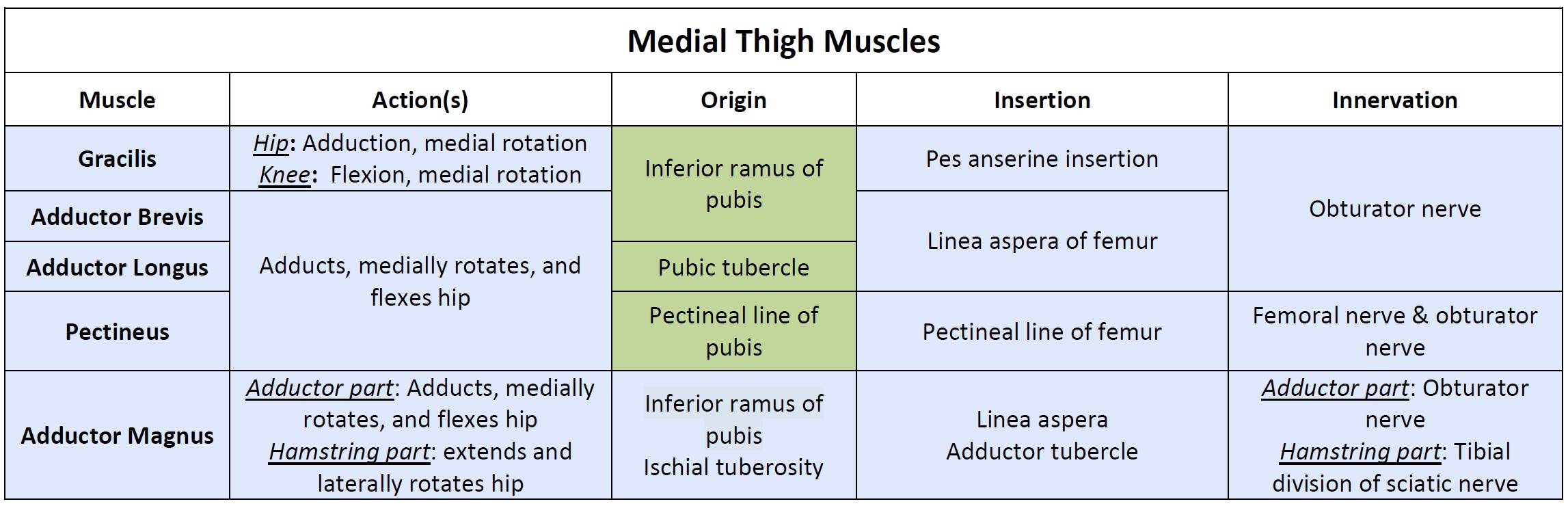

The medial thigh muscles all act to adduct the hip (among other functions that differ by muscle). These muscles include the adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, pectineus, and gracilis. The gracilis also crosses the knee, inserting at the pes anserine insertion. As a result, it also assists with flexion and medial rotation at the knee.

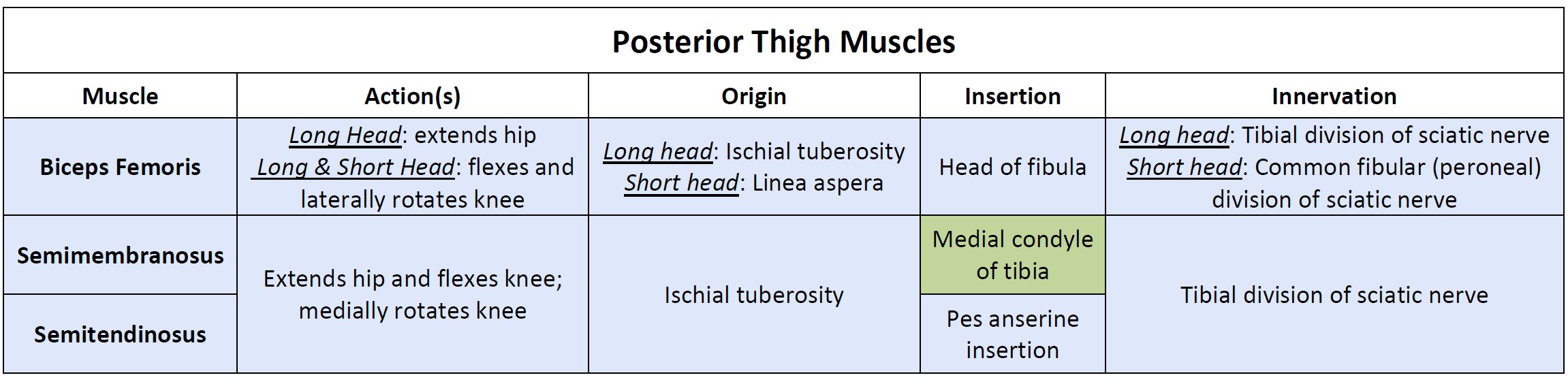

The posterior muscles of the thigh flex the knee and extend the hip. They are known as the hamstring group, and they include the biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus. The semimembranosus and semitendinosus cross the knee medially, while the biceps femoris crosses the knee laterally. As the name indicates, the biceps femoris has two heads, a long head and a short head. The long head of biceps femoris crosses the hip, but the short head originates on the linea aspera of the femur. As a result, it only acts on the knee. The two heads merge into a common tendon that inserts at the fibular head.

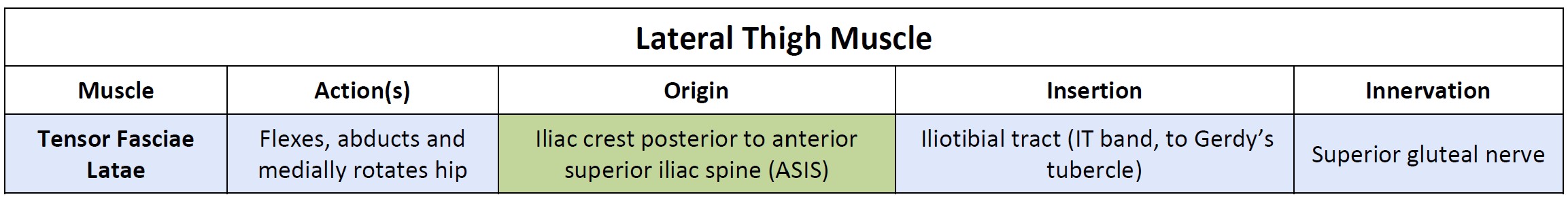

There is only one muscle in the lateral thigh. The tensor fascia latae is a thick, squarish muscle in the superior aspect of the lateral thigh. It acts as a synergist of the gluteus medius and iliopsoas in flexing and abducting the thigh. It also helps stabilize the lateral aspect of the knee by pulling on the iliotibial tract (IT band), making it taut.