Module 8: Lymphatic System

Learning Objectives:

By the end of this module, students will be able to:

- Explain the structure and function of the lymphatic vessels.

- Identify the functions of the lymphatic system.

- Describe the relationship between the lymphatic system and immune function.

- Predict the consequences of the anatomy of the lymphatic system (e.g., cancer spread) and lymphatic system dysfunction.

- Describe the organs of the lymphatic system and their functions in the immune system.

Terms to Know

|

Vessels

Lymphatic System

|

Lymphatic System (continued)

|

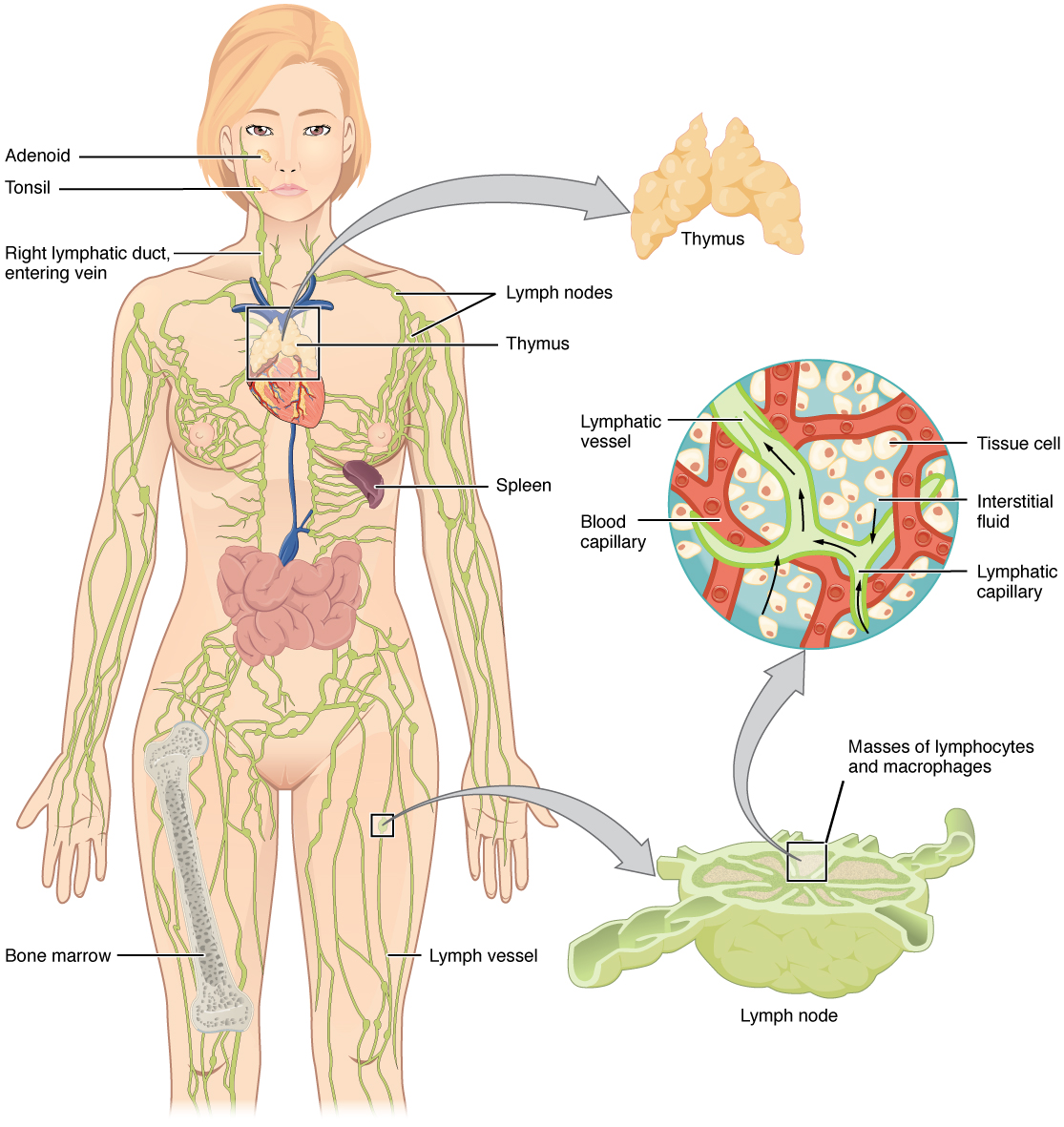

The immune system is the complex collection of cells and organs that destroys or neutralizes pathogens that otherwise cause disease or death. For most people, the lymphatic system is associated with the immune system to such a degree that the two systems are virtually indistinguishable. The lymphatic system is the system of vessels, cells, and organs that carries excess fluids to the bloodstream and filter pathogens from the blood. The swelling of lymph nodes during an infection and the transport of lymphocytes via the lymphatic vessels are two examples of the many connections between these critical organ systems.

Lymph contains a liquid matrix and white blood cells. Lymphatic capillaries are extremely permeable, allowing larger molecules and excess fluid from interstitial spaces to enter the lymphatic vessels. Lymph drains into blood vessels, delivering molecules to the blood that could not directly enter the bloodstream. In this way, specialized lymphatic capillaries transport absorbed fats away from the intestine and deliver these molecules to the blood.

Functions of the Lymphatic System

A major function of the lymphatic system is to drain body fluids and return them to the bloodstream. Blood pressure causes leakage of fluid from the capillaries, resulting in fluid accumulation in the interstitial space—that is, spaces between individual cells in the tissues. In humans, 20 liters of plasma are released into the tissues’ interstitial space each day due to capillary filtration. Once this filtrate is out of the bloodstream and in the tissue spaces, it is referred to as interstitial fluid. Of this, 17 liters are reabsorbed directly by the blood vessels. But what happens to the remaining three liters? This is where the lymphatic system comes into play. It drains the excess fluid and empties it back into the bloodstream via a series of vessels, trunks, and ducts. Lymph is the term used to describe interstitial fluid once it has entered the lymphatic system. When the lymphatic system is damaged in some way, such as by being blocked by cancer cells or destroyed by injury, protein-rich interstitial fluid accumulates (sometimes “backs up” from the lymph vessels) in the tissue spaces. This inappropriate accumulation of fluid referred to as lymphedema may lead to serious medical consequences.

As the vertebrate immune system evolved, the network of lymphatic vessels became convenient avenues for transporting the cells of the immune system. Additionally, the transport of dietary lipids and fat-soluble vitamins absorbed in the gut uses this system.

Cells of the immune system not only use lymphatic vessels to make their way from interstitial spaces back into the circulation, but they also use lymph nodes as major staging areas for the development of critical immune responses. A lymph node is one of the small, bean-shaped organs located throughout the lymphatic system.

Structure of the Lymphatic System

The lymphatic vessels begin as blind-ending or closed at one end, capillaries, which feed into larger and larger lymphatic vessels and eventually empty into the bloodstream by a series of ducts. Along the way, the lymph travels through the lymph nodes, which are commonly found near the groin, armpits, neck, chest, and abdomen. Humans have about 500–600 lymph nodes throughout the body.

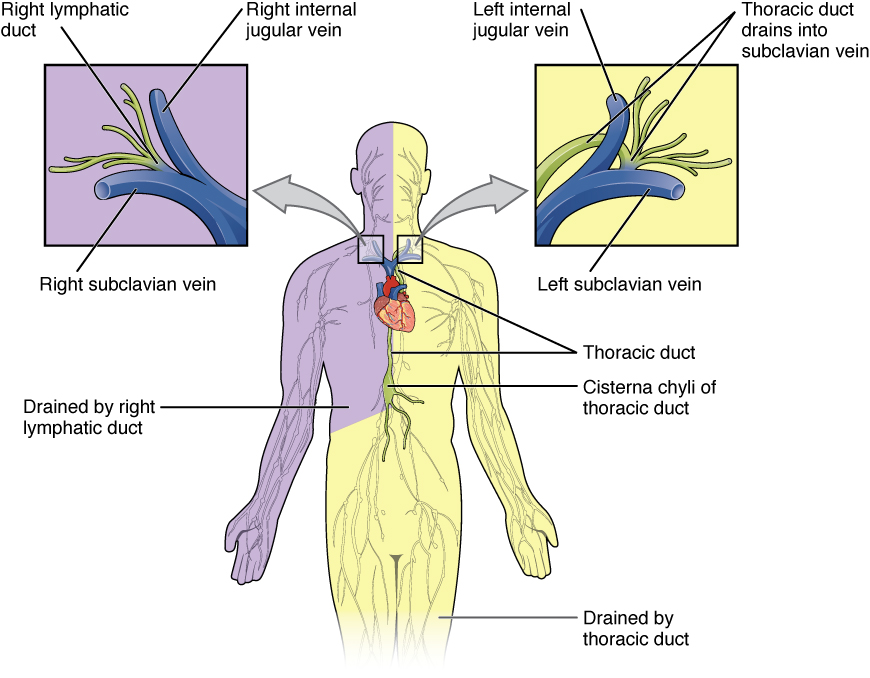

A major distinction between the lymphatic and cardiovascular systems in humans is that lymph is not actively pumped by the heart but is forced through the vessels by the movements of the body, the contraction of skeletal muscles during body movements, and breathing. One-way valves in lymphatic vessels keep the lymph moving toward the heart. Lymph flows from the lymphatic capillaries through lymphatic vessels. It then is dumped into the circulatory system via the lymphatic ducts located at the junction of the jugular and subclavian veins in the neck.

Lymphatic Capillaries

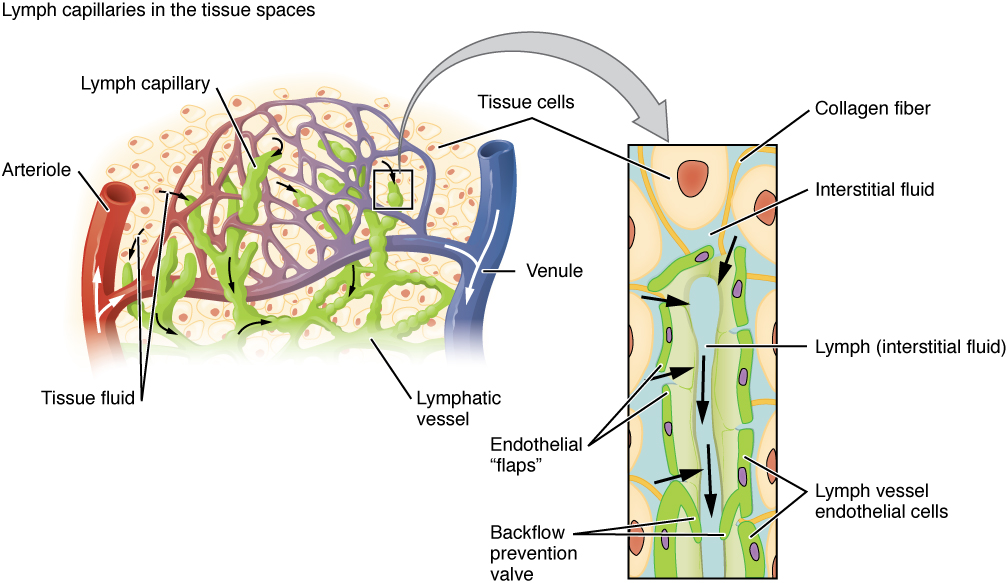

Lymphatic capillaries are vessels where interstitial fluid enters the lymphatic system to become lymph fluid. Located in almost every tissue in the body, these vessels are interlaced among the arterioles and venules of the circulatory system in the soft connective tissues of the body. Exceptions are the central nervous system, bone marrow, bones, teeth, and the cornea of the eye, which do not contain lymph vessels.

Lymphatic capillaries are formed by simple squamous endothelial cells and represent the open end of the system, allowing interstitial fluid to flow into them via overlapping cells. When interstitial pressure is low, the endothelial flaps close to prevent “backflow.” As interstitial pressure increases, the spaces between the cells open up, allowing the fluid to enter. The entry of fluid into lymphatic capillaries is also enabled by the collagen filaments that anchor the capillaries to surrounding structures. As interstitial pressure increases, the filaments pull on the endothelial cell flaps, opening them even further to allow easy entry of fluid.

Larger Lymphatic Vessels, Trunks, and Ducts

The lymphatic capillaries empty into larger lymphatic vessels, which are similar to veins in terms of their three-tunic structure and the presence of valves. These one-way valves are located fairly close to one another, and each one causes a bulge in the lymphatic vessel, giving the vessels a beaded appearance.

The superficial and deep lymphatics eventually merge to form larger lymphatic vessels known as lymphatic trunks. On the right side of the body, the right sides of the head, thorax, and right upper limb drain lymph fluid into the right subclavian vein via the right lymphatic duct. On the left side of the body, the remaining portions of the body drain into the larger thoracic duct, which drains into the left subclavian vein. The thoracic duct itself begins just beneath the diaphragm in the cisterna chyli, a sac-like chamber that receives lymph from the lower abdomen, pelvis, and lower limbs by way of the left and right lumbar trunks and the intestinal trunk.

The overall drainage system of the body is asymmetrical. The right lymphatic duct receives lymph from only the upper right side of the body. The lymph from the rest of the body enters the bloodstream through the thoracic duct via all the remaining lymphatic trunks. In general, lymphatic vessels of the subcutaneous tissues of the skin, that is, the superficial lymphatics, follow the same routes as veins. In contrast, the deep lymphatic vessels of the viscera generally follow the paths of arteries.

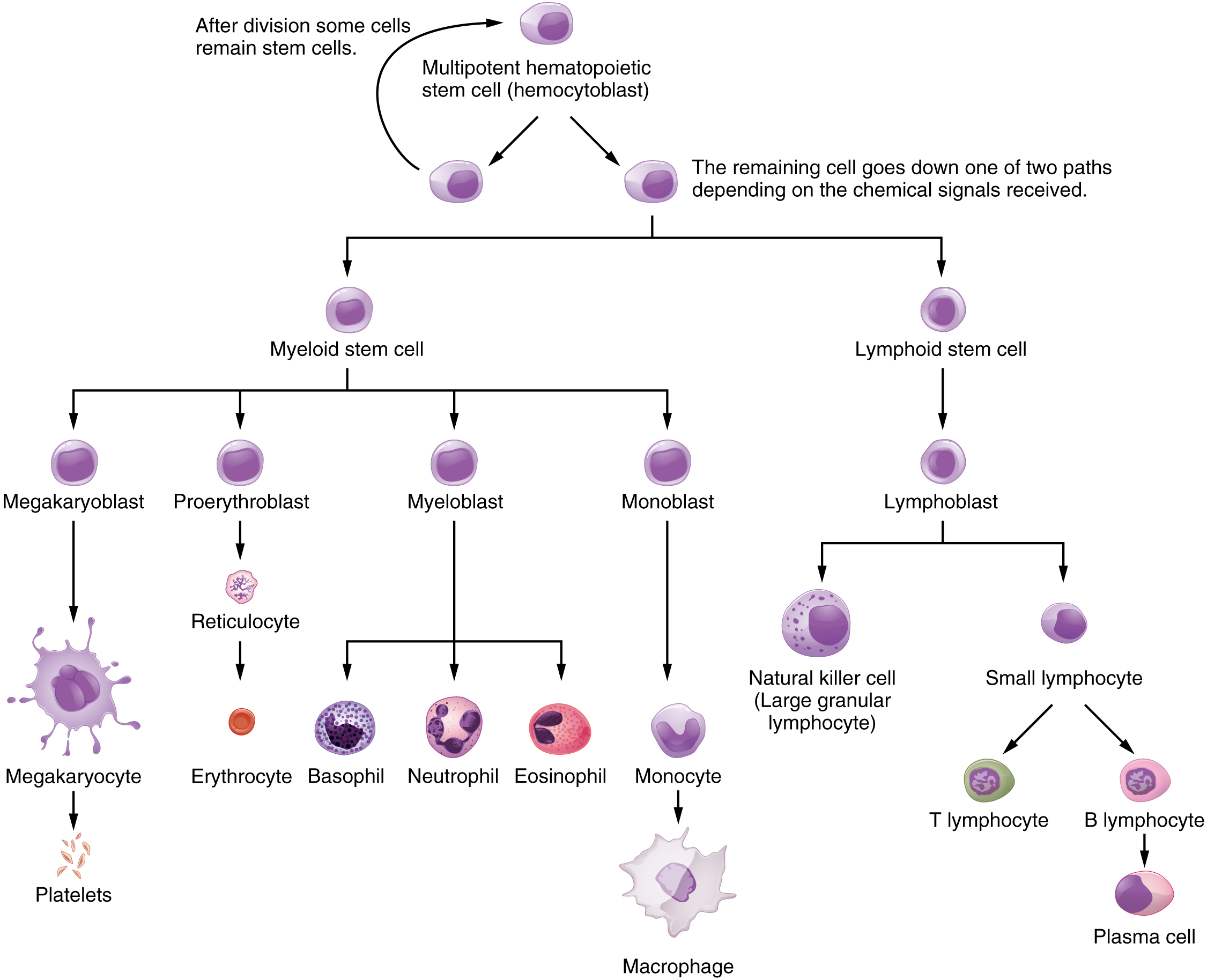

Lymphocytes: B Cells, T Cells, and Natural Killer Cells

Lymphocytes are the primary cells of adaptive immune responses. The two basic types of lymphocytes, B cells and T cells are identical morphologically, with a large central nucleus surrounded by a thin layer of cytoplasm. They are distinguished from each other by their surface protein markers and the molecules they secrete. While B cells mature in the red bone marrow and T cells mature in the thymus, they both initially develop from bone marrow. T cells migrate from bone marrow to the thymus gland, where they further mature. B cells and T cells are found in many parts of the body, circulating in the bloodstream and lymph, and residing in secondary lymphoid organs, including the spleen and lymph nodes, which will be described later in this section. The human body contains approximately 1012 lymphocytes.

B Cells

B cells are immune cells that function primarily by producing antibodies. An antibody is any of the group of proteins that binds specifically to pathogen-associated molecules known as antigens. An antigen is a chemical structure on the surface of a pathogen that binds to T or B lymphocyte antigen receptors. Once activated by binding to antigen, B cells differentiate into cells that secrete a soluble form of their surface antibodies. These activated B cells are known as plasma cells. A plasma cell is a B cell that has differentiated in response to antigen binding and has thereby gained the ability to secrete soluble antibodies. These cells differ in morphology from standard B and T cells. They contain a large amount of cytoplasm packed with the protein-synthesizing machinery known as the rough endoplasmic reticulum.

T Cells

On the other hand, the T cell does not secrete antibody but performs a variety of functions in the adaptive immune response. Different T cell types have the ability to either secrete soluble factors that communicate with other cells of the adaptive immune response or destroy cells infected with intracellular pathogens.

Natural Killer Cells

A third important lymphocyte is the natural killer cell, a participant in the innate immune response. A natural killer cell (NK) is a circulating blood cell containing cytotoxic (cell-killing) granules in its extensive cytoplasm. It shares this mechanism with the cytotoxic T cells of the adaptive immune response. NK cells are among the body’s first lines of defense against viruses and certain types of cancer.

Key Takeaways

- B Cells (and plasma cells)

- Generate diverse antibodies (secrete antibodies)

- T Cells

- Recognize antibodies on infected cells

- Secrete chemical messengers

- Destroy cells infected with intracellular pathogens

- NK Cells

- Among the first line of defense

- Destroy virally infected cells/certain cancerous cells

Primary Lymphoid Organs and Lymphocyte Development

Understanding the differentiation and development of B and T cells is critical to understanding the adaptive immune response. Through this process, the body (ideally) learns to destroy only pathogens and leaves the body’s own cells relatively intact. The primary lymphoid organs are the bone marrow and thymus gland. The lymphoid organs are where lymphocytes mature, proliferate, and are selected, which enables them to attack pathogens without harming the cells of the body.

Bone Marrow

In the embryo, blood cells are made in the yolk sac. As development proceeds, this function is taken over by the spleen, lymph nodes, and liver. Later, the bone marrow takes over most hematopoietic functions, although the final stages of the differentiation of some cells may take place in other organs. The red bone marrow is a loose collection of cells where hematopoiesis occurs, and the yellow bone marrow is a site of energy storage, which consists largely of fat cells. The B cell undergoes nearly all of its development in the red bone marrow, whereas the immature T cell, called a thymocyte, leaves the bone marrow and matures largely in the thymus gland.

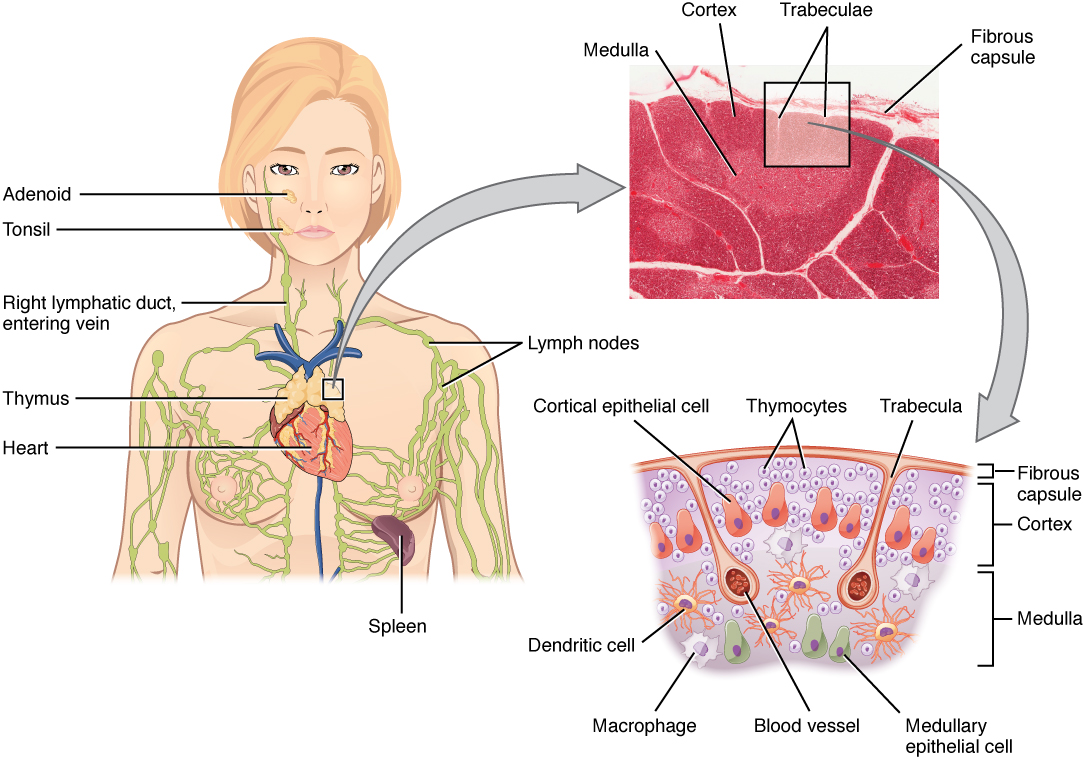

Thymus

The thymus gland is a bilobed organ found in the space between the sternum and the aorta of the heart. Connective tissue holds the lobes closely together but also separates them and forms a capsule.

Secondary Lymphoid Organs and their Roles in Active Immune Responses

Lymphocytes develop and mature in the primary lymphoid organs, but they mount immune responses from the secondary lymphoid organs. A naïve lymphocyte is one that has left the primary organ and entered a secondary lymphoid organ. Naïve lymphocytes are fully functional immunologically but have yet to encounter an antigen to respond to. In addition to circulating in the blood and lymph, lymphocytes concentrate in secondary lymphoid organs, including the lymph nodes, spleen, and lymphoid nodules. All of these tissues have many features in common, including the following:

- The presence of lymphoid follicles, the sites of the formation of lymphocytes, with specific B cell-rich and T cell-rich areas

- An internal structure of reticular fibers with associated fixed macrophages

- Germinal centers, which are the sites of rapidly dividing and differentiating B lymphocytes

- Specialized post-capillary vessels are known as high endothelial venules; the cells lining these venules are thicker and more columnar than normal endothelial cells, which allow cells from the blood to enter these tissues directly.

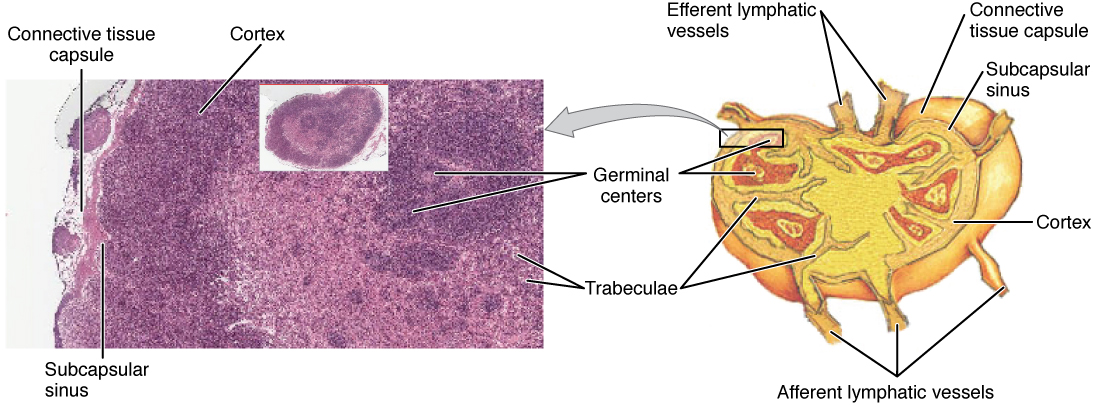

Lymph Nodes

Lymph nodes function to remove debris and pathogens from the lymph and are sometimes referred to as the “filters of the lymph.” Any bacteria that infect the interstitial fluid are taken up by the lymphatic capillaries and transported to a regional lymph node. Dendritic cells and macrophages within this organ internalize and kill many of the pathogens that pass through, thereby removing them from the body. The lymph node is also the site of adaptive immune responses mediated by T cells, B cells, and accessory cells of the adaptive immune system. Like the thymus, the bean-shaped lymph nodes are surrounded by a tough capsule of connective tissue and are separated into compartments by trabeculae, the extensions of the capsule. In addition to the structure provided by the capsule and trabeculae, the structural support of the lymph node is provided by a series of reticular fibers laid down by fibroblasts.

The major routes into the lymph node are via afferent lymphatic vessels. Cells and lymph fluid that leave the lymph node may do so by another set of vessels known as the efferent lymphatic vessels. Lymph enters the lymph node via the subcapsular sinus, which is occupied by dendritic cells, macrophages, and reticular fibers. Within the lymph node’s cortex are lymphoid follicles, which consist of germinal centers of rapidly dividing B cells surrounded by a layer of T cells and other accessory cells. As the lymph continues to flow through the node, it enters the medulla, which consists of medullary cords of B cells and plasma cells, and the medullary sinuses where the lymph collects before leaving the node via the efferent lymphatic vessels.

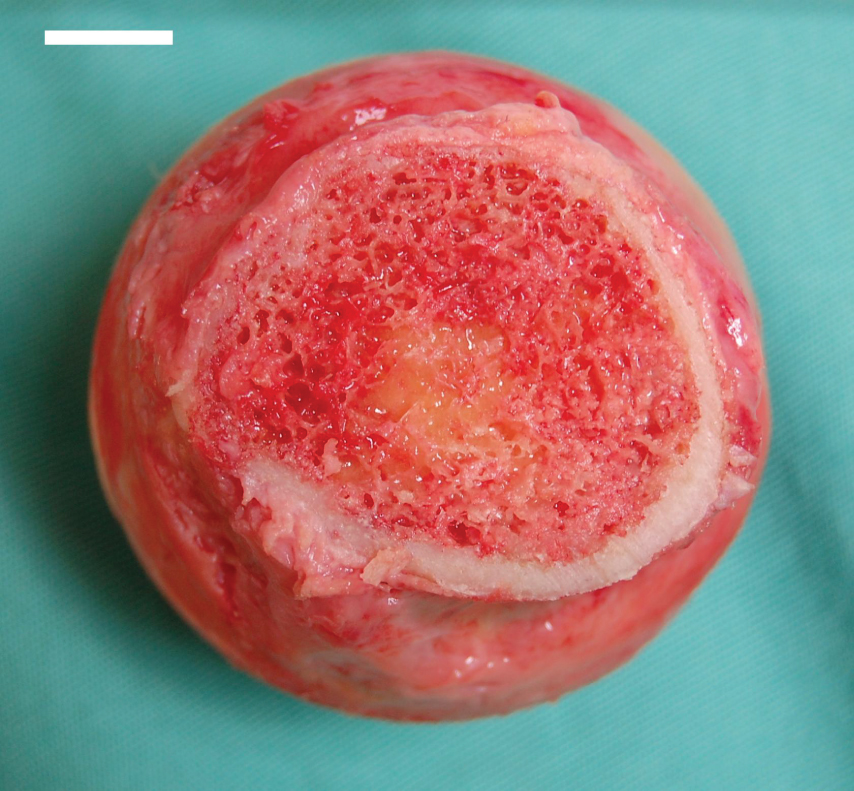

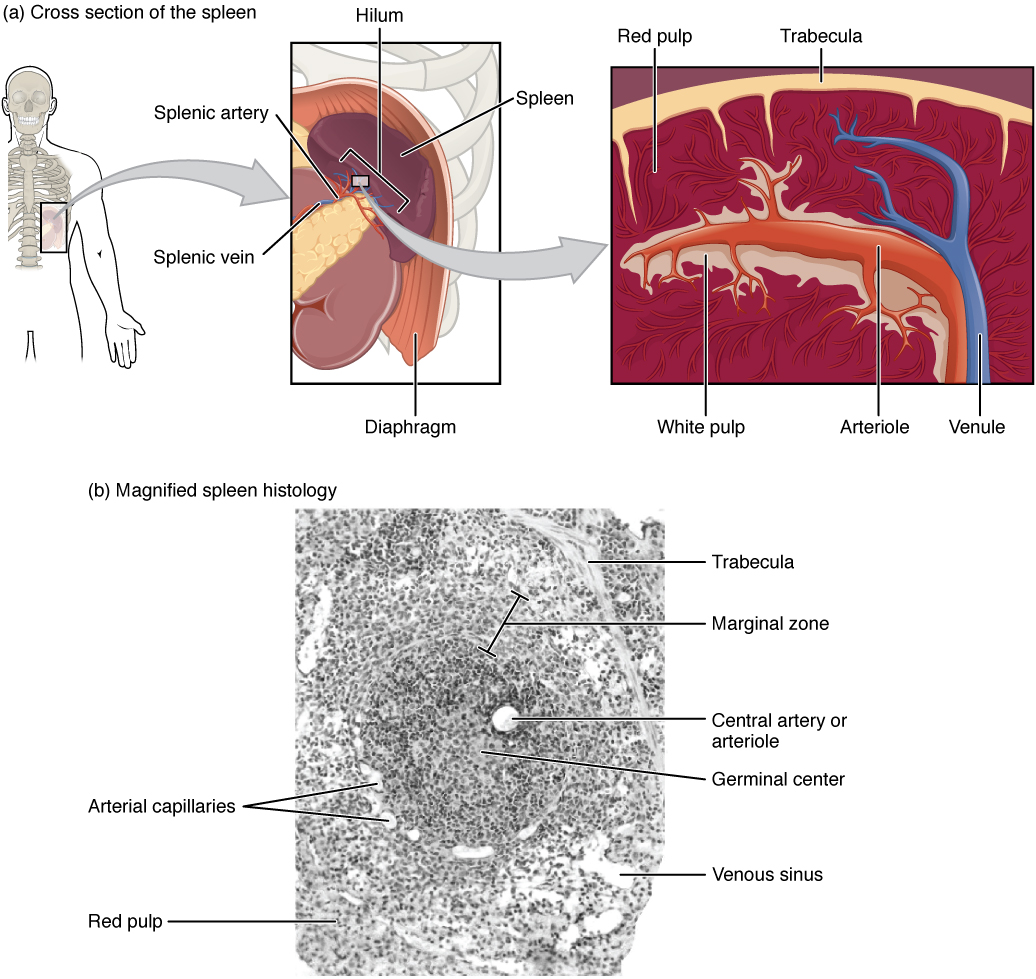

Spleen

In addition to the lymph nodes, the spleen is a major secondary lymphoid organ. The spleen is a fragile organ without a strong capsule and is dark red due to its extensive vascularization. The spleen is sometimes called the “filter of the blood” because of its extensive vascularization and the presence of macrophages and dendritic cells that remove microbes and other materials from the blood, including dying red blood cells. The spleen also functions as the location of immune responses to blood-borne pathogens.

The spleen is also divided by trabeculae of connective tissue. Within each splenic nodule is an area of red pulp, consisting of mostly red blood cells and white pulp, which resembles the lymphoid follicles of the lymph nodes. Upon entering the spleen, the splenic artery splits into several arterioles (surrounded by white pulp) and eventually into sinusoids. Blood from the capillaries subsequently collects in the venous sinuses and leaves via the splenic vein. The red pulp consists of reticular fibers with fixed macrophages attached, free macrophages, and other cells typical of the blood, including some lymphocytes. The white pulp surrounds a central arteriole and consists of germinal centers of dividing B cells surrounded by T cells and accessory cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells. Thus, the red pulp primarily functions as a blood filtration system, using cells of the relatively nonspecific immune response, and white pulp is where adaptive T and B cell responses are mounted.

Lymphoid Nodules

The other lymphoid tissues, the lymphoid nodules, have a simpler architecture than the spleen and lymph nodes in that they consist of a dense cluster of lymphocytes without a surrounding fibrous capsule. These nodules are located in the respiratory and digestive tracts, areas routinely exposed to environmental pathogens.

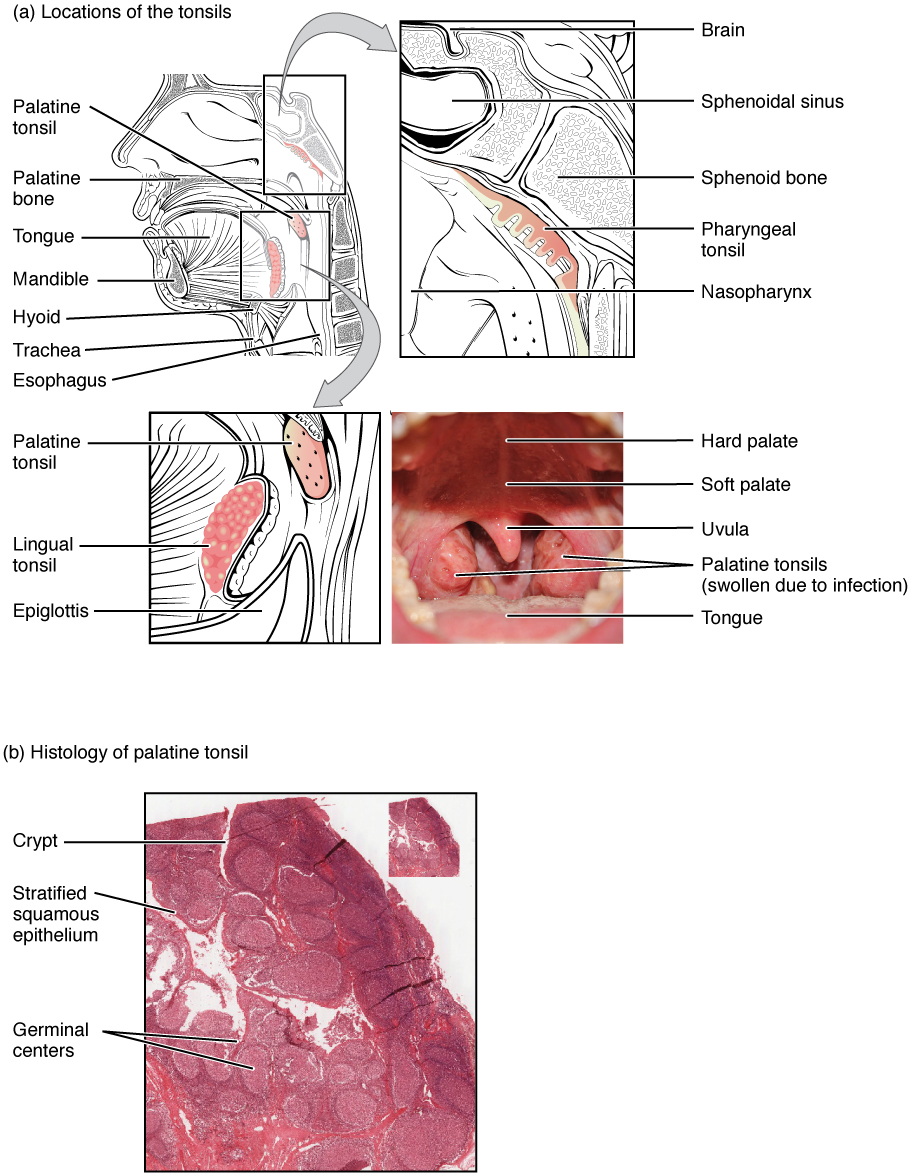

Tonsils are lymphoid nodules located along the pharynx’s inner surface and are important in developing immunity to oral pathogens. The tonsil located at the back of the throat, the pharyngeal tonsil, is sometimes referred to as the adenoid when swollen. Such swelling is an indication of an active immune response to infection. Histologically, tonsils do not contain a complete capsule, and the epithelial layer invaginates deeply into the interior of the tonsil to form tonsillar crypts. These structures, which accumulate all sorts of materials taken into the body through eating and breathing, actually “encourage” pathogens to penetrate deep into the tonsillar tissues, where they are acted upon by numerous lymphoid follicles and eliminated. This seems to be the major function of tonsils—to help children’s bodies recognize, destroy, and develop immunity to common environmental pathogens so that they will be protected in their later lives. Tonsils are often removed in those children who have recurring throat infections, especially those involving the palatine tonsils on either side of the throat, whose swelling may interfere with their breathing and/or swallowing.

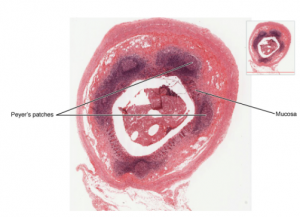

MALT

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) consists of an aggregate of lymphoid follicles directly associated with the mucous membrane epithelia. MALT makes up dome-shaped structures found underlying the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract, breast tissue, lungs, and eyes. Peyer’s patches, a type of MALT in the small intestine, are especially important for immune responses against ingested substances. Peyer’s patches contain specialized endothelial cells called M (or microfold) cells that sample material from the intestinal lumen and transport it to nearby follicles so that adaptive immune responses to potential pathogens can be mounted. A similar process occurs involving MALT in the mucosa and submucosa of the appendix. A blockage of the lumen triggers these cells to elicit an inflammatory response that can lead to appendicitis.

Aging and the Lymphatic System – FYI (For Your Information -> you will not be assessed on this content)

By the year 2050, 25 percent of the United States population will be 60 years of age or older. The CDC estimates that 80 percent of those 60 years and older have one or more chronic diseases associated with deficiencies of the immune systems. This loss of immune function with age is called immunosenescence. To treat this growing population, medical professionals must better understand the aging process. One major cause of age-related immune deficiencies is thymic involution, the shrinking of the thymus gland that begins at birth, at a rate of about three percent tissue loss per year, and continues until 35–45 years of age, when the rate declines to about one percent loss per year for the rest of one’s life. At that pace, the total loss of thymic epithelial tissue and thymocytes would occur at about 120 years of age. Thus, this age is a theoretical limit to a healthy human lifespan.

Thymic involution has been observed in all vertebrate species that have a thymus gland. It is also known that hormone levels can alter thymic involution. Sex hormones such as estrogen and testosterone enhance involution. The hormonal changes in pregnant women cause a temporary thymic involution that reverses itself when the size of the thymus and its hormone levels return to normal, usually after lactation ceases. What does all this tell us? Can we reverse immunosenescence, or at least slow it down? The potential is there for using thymic transplants from younger donors to keep the thymic output of naïve T cells high. Gene therapies that target gene expression are also seen as future possibilities. The more we learn through immunosenescence research, the more opportunities there will be to develop therapies, even though these therapies will likely take decades to develop. The ultimate goal is for everyone to live and be healthy longer, but there may be limits to immortality imposed by our genes and hormones.