M10Q4: Explaining Solubility and Surface Tension through IMFs

Introduction

In this section we continue applying our understanding of IMFs to predict trends in physical properties. Here, we look at how to apply IMF predictions to solubility, surface tension, and adhesive and cohesive forces.

Learning Objectives for Explaining Solubility and Surface Tension through IMFs

- Connect trends in physical properties with relative strength of intermolecular forces.

- Predict solubility with the guidance that “like dissolves like”.

| Solubility | Solutions of Gases in Liquids | Solutions of Liquids in Liquids | Solutions of Solids in Liquids | - Compare relative surface tension and viscosity of two similar compounds.

| Surface Tension | Viscosity | - Use adhesive and cohesive forces to explain capillary forces.

| Cohesive and Adhesive Forces | Capillary Forces |

- Predict solubility with the guidance that “like dissolves like”.

| Key Concepts and Summary | Glossary | End of Section Exercises |

Solubility

Imagine adding a small amount of salt to a glass of water, stirring until all the salt has dissolved, and then adding a bit more. You can repeat this process until the salt concentration of the solution reaches its natural limit, a limit determined primarily by the relative strengths of the solute-solute, solute-solvent, and solvent-solvent attractive forces discussed in the previous two sections of this module. You can be certain that you have reached this limit because, no matter how long you stir the solution, undissolved salt remains. The concentration of salt in the solution at this point is known as its solubility.

The solubility of a solute in a particular solvent is the maximum concentration that may be achieved under given conditions when the dissolution process is at equilibrium. Referring to the example of salt in water:

NaCl(s) ⇌ Na+(aq) + Cl–(aq)

When a solute’s concentration is equal to its solubility, the solution is said to be saturated with that solute. If the solute’s concentration is less than its solubility, the solution is said to be unsaturated. A solution that contains a relatively low concentration of solute is called dilute, and one with a relatively high concentration is called concentrated.

If we add more salt to a saturated solution of salt, we see it fall to the bottom and no more seems to dissolve. In fact, the added salt does dissolve, as represented by the forward direction of the dissolution equation. Accompanying this process, dissolved salt will precipitate, as depicted by the reverse direction of the equation. The system is said to be at equilibrium when these two reciprocal processes are occurring at equal rates, and so the amount of undissolved and dissolved salt remains constant. Support for the simultaneous occurrence of the dissolution and precipitation processes is provided by noting that the number and sizes of the undissolved salt crystals will change over time, though their combined mass will remain the same.

Use this interactive simulation to prepare various saturated solutions.

Solutions may be prepared in which a solute concentration exceeds its solubility. Such solutions are said to be supersaturated, and they are interesting examples of nonequilibrium states. For example, the carbonated beverage in an open container that has not yet “gone flat” is supersaturated with carbon dioxide gas; given time, the CO2 concentration will decrease until it reaches its equilibrium value.

Watch this impressive video showing the precipitation of sodium acetate from a supersaturated solution.

Solutions of Gases in Liquids

In an earlier section of this module, the effect of intermolecular attractive forces on solution formation was discussed. The chemical structures of the solute and solvent dictate the types of forces possible and, consequently, are important factors in determining solubility. For example, under similar conditions, the water solubility of oxygen is approximately three times greater than that of helium, but 100 times less than the solubility of chloromethane, CHCl3. Considering the role of the solvent’s chemical structure, note that the solubility of oxygen in the liquid hydrocarbon hexane, C6H14, is approximately 20 times greater than it is in water.

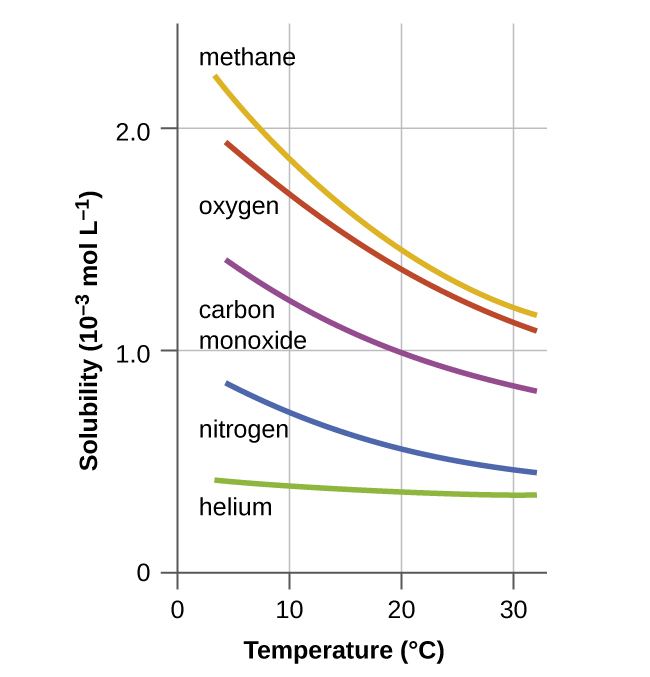

Other factors also affect the solubility of a given substance in a given solvent. Temperature is one such factor, with gas solubility typically decreasing as temperature increases (Figure 1). This is one of the major impacts resulting from the thermal pollution of natural bodies of water.

When the temperature of a river, lake, or stream is raised abnormally high, usually due to the discharge of hot water from some industrial process, the solubility of oxygen in the water is decreased. Decreased levels of dissolved oxygen may have serious consequences for the health of the water’s ecosystems and, in severe cases, can result in large-scale fish kills (Figure 2).

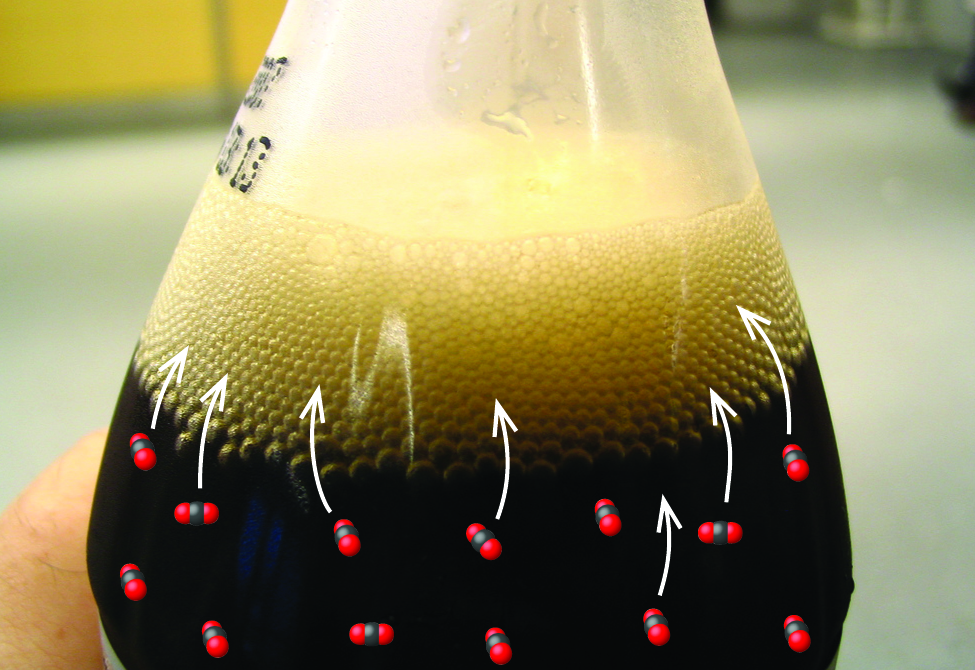

The solubility of a gaseous solute is also affected by the partial pressure of solute in the gas to which the solution is exposed. Gas solubility increases as the pressure of the gas increases. Carbonated beverages provide a nice illustration of this relationship. The carbonation process involves exposing the beverage to a relatively high pressure of carbon dioxide gas and then sealing the beverage container, thus saturating the beverage with CO2 at this pressure. When the beverage container is opened, a familiar hiss is heard as the carbon dioxide gas pressure is released, and some of the dissolved carbon dioxide is typically seen leaving solution in the form of small bubbles (Figure 3). At this point, the beverage is supersaturated with carbon dioxide and, with time, the dissolved carbon dioxide concentration will decrease to its equilibrium value and the beverage will become “flat.”

Chemistry in Real Life: Decompression Sickness or “The Bends”

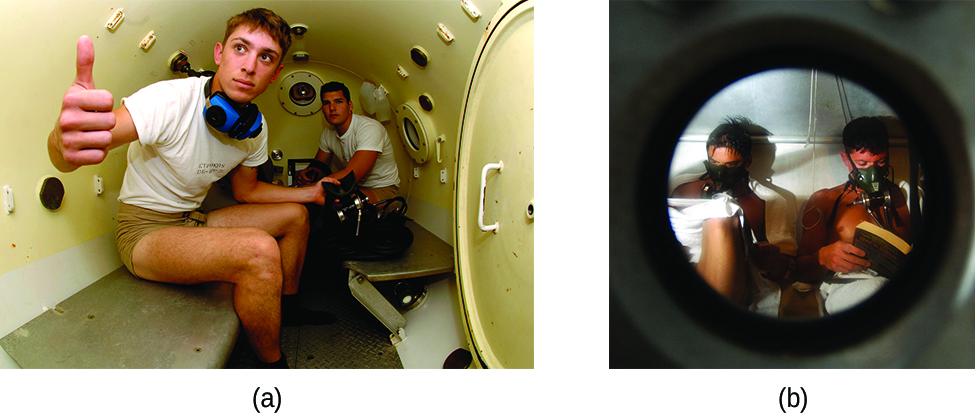

Decompression sickness (DCS), or “the bends,” is an effect of the increased pressure of the air inhaled by scuba divers when swimming underwater at considerable depths. In addition to the pressure exerted by the atmosphere, divers are subjected to additional pressure due to the water above them, experiencing an increase of approximately 1 atm for each 10 m of depth. Therefore, the air inhaled by a diver while submerged contains gases at the corresponding higher ambient pressure, and the concentrations of the gases dissolved in the diver’s blood are proportionally higher.

As the diver ascends to the surface of the water, the ambient pressure decreases and the dissolved gases becomes less soluble. If the ascent is too rapid, the gases escaping from the diver’s blood may form bubbles that can cause a variety of symptoms ranging from rashes and joint pain to paralysis and death. To avoid DCS, divers must ascend from depths at relatively slow speeds (10 or 20 m/min) or otherwise make several decompression stops, pausing for several minutes at given depths during the ascent. When these preventive measures are unsuccessful, divers with DCS are often provided hyperbaric oxygen therapy in pressurized vessels called decompression (or recompression) chambers (Figure 4).

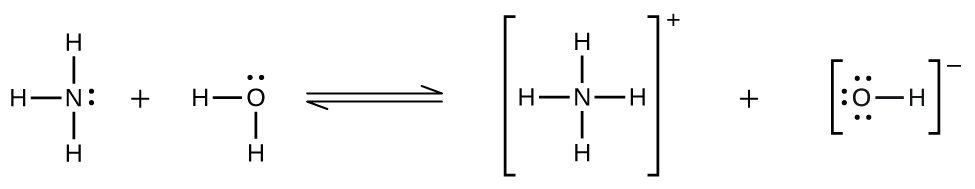

Deviations from expected behavior are observed when a chemical reaction takes place between the gaseous solute and the solvent. Thus, for example, the solubility of ammonia in water does not increase as rapidly with increasing pressure as predicted by the law because ammonia, being a base, reacts to some extent with water to form ammonium ions and hydroxide ions.

Gases can form supersaturated solutions. If a solution of a gas in a liquid is prepared either at low temperature or under pressure (or both), then as the solution warms or as the gas pressure is reduced, the solution may become supersaturated. In 1986, more than 1700 people in Cameroon were killed when a cloud of gas, almost certainly carbon dioxide, bubbled from Lake Nyos (Figure 5), a deep lake in a volcanic crater. The water at the bottom of Lake Nyos is saturated with carbon dioxide by volcanic activity beneath the lake. It is believed that the lake underwent a turnover due to gradual heating from below the lake, and the warmer, less-dense water saturated with carbon dioxide reached the surface. Consequently, tremendous quantities of dissolved CO2 were released, and the colorless gas, which is denser than air, flowed down the valley below the lake and suffocated humans and animals living in the valley.

Solutions of Liquids in Liquids

We know that some liquids mix with each other in all proportions; in other words, they have infinite mutual solubility and are said to be miscible. Ethanol, sulfuric acid, and ethylene glycol (popular for use as antifreeze, pictured in Figure 6) are examples of liquids that are completely miscible with water. Two-cycle motor oil is miscible with gasoline.

Liquids that mix with water in all proportions are usually polar substances or substances that form hydrogen bonds. For such liquids, the dipole-dipole attractions (or hydrogen bonding) of the solute molecules with the solvent molecules are at least as strong as those between molecules in the pure solute or in the pure solvent. Hence, the two kinds of molecules mix easily. Likewise, nonpolar liquids are miscible with each other because there is no appreciable difference in the strengths of solute-solute, solvent-solvent, and solute-solvent intermolecular attractions. The solubility of polar molecules in polar solvents and of nonpolar molecules in nonpolar solvents is, again, an illustration of the chemical axiom “like dissolves like.”

Two liquids that do not mix to an appreciable extent are called immiscible. Layers are formed when we pour immiscible liquids into the same container. Gasoline, oil (Figure 7), benzene, carbon tetrachloride, some paints, and many other nonpolar liquids are immiscible with water. The attraction between the molecules of such nonpolar liquids and polar water molecules is ineffectively weak. The only strong attractions in such a mixture are between the water molecules, so they effectively squeeze out the molecules of the nonpolar liquid. The distinction between immiscibility and miscibility is really one of degrees, so that miscible liquids are of infinite mutual solubility, while liquids said to be immiscible are of very low (though not zero) mutual solubility.

Two liquids, such as bromine and water, that are of moderate mutual solubility are said to be partially miscible. Two partially miscible liquids usually form two layers when mixed. In the case of the bromine and water mixture, the upper layer is water, saturated with bromine, and the lower layer is bromine saturated with water. Since bromine is nonpolar, and, thus, not very soluble in water, the water layer is only slightly discolored by the bright orange bromine dissolved in it. Since the solubility of water in bromine is very low, there is no noticeable effect on the dark color of the bromine layer (Figure 8).

Demonstration: Solubility of I2 in H2O vs. CCl4

Set up. The following demonstration illustrates how intermolecular forces determine solubility. Initially, an Erlenmeyer flask contains I2 dissolved in water (i.e., I2(aq)). Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4(ℓ)), a colorless liquid, is added to a graduated cylinder. When the I2(aq) is added to the graduated cylinder, the I2(aq) is less dense and therefore sits on top of the CCl4(ℓ). The iodine remains fully in the aqueous layer and the water and CCl4(ℓ) are immiscible, forming two distinct layers. The graduated cylinder is then shaken to mix the contents thoroughly.

If the iodine is more soluble in water, the contents will settle and be similar as before agitation (the contents will only look the same if the iodine is completely insoluble in CCl4). If the iodine is more soluble in CCl4, the contents will settle and the iodine will be primarily located on the bottom half of the graduated cylinder, dissolved in CCl4. If the iodine is equally soluble in water and CCl4, the iodine will be distributed throughout the graduated cylinder.

Prediction. Before watching the demonstration, make a prediction about which layer (water or CCl4 or both) the majority of the iodine will reside in after the contents settle.

Explanation. The intermolecular forces between I2 molecules are dispersion forces; the intermolecular forces between water molecules are dispersion forces and hydrogen bonds. The iodine is fully dissolved in the water and the I2 molecules interact with the water molecules primarily via dispersion forces. The intermolecular forces between CCl4(ℓ) are also dispersion forces. Once the contents are agitated and allowed to settle, however, the purple iodine is primarily located in the lower CCl4 layer. This indicates that the iodine is more soluble in CCl4 (a slight yellow color is still seen in the water layers as some iodine is still dissolved in water).

To understand why, think about the different IMFs among water molecules and among CCl4 molecules: when iodine interacts with water molecules, hydrogen bonds and dispersion forces are broken between water molecules and only dispersion forces are formed between water and I2. When iodine interacts with CCl4, however, dispersion forces are disrupted between CCl4 molecules and formed between CCl4 and I2. The disruption of hydrogen bonds in water makes iodine more soluble in CCl4, where it dissolves without disrupting hydrogen bonds.

Solutions of Solids in Liquids

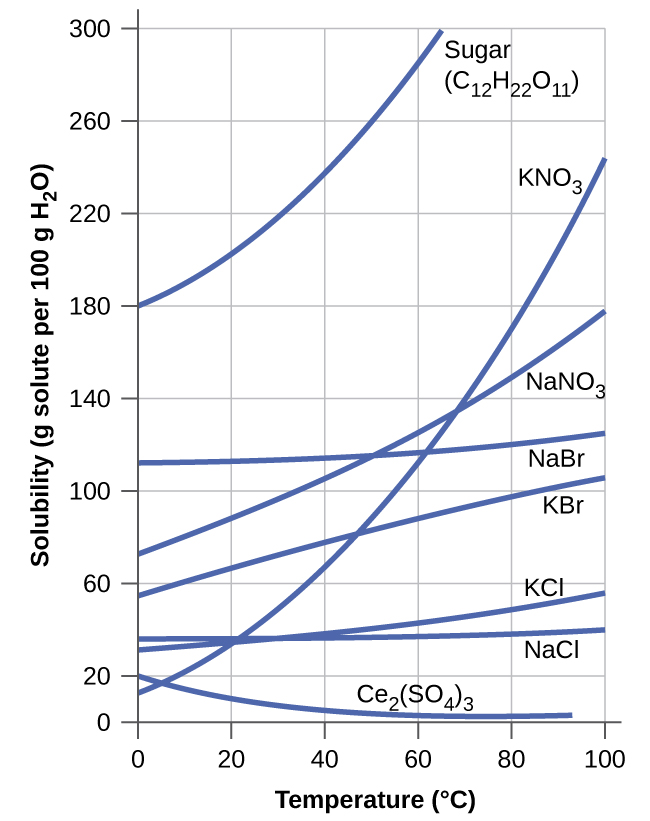

The dependence of solubility on temperature for a number of inorganic solids in water is shown by the solubility curves in Figure 9. Reviewing these data indicate a general trend of increasing solubility with temperature, although there are exceptions, as illustrated by the ionic compound cerium sulfate (Ce2(SO4)3).

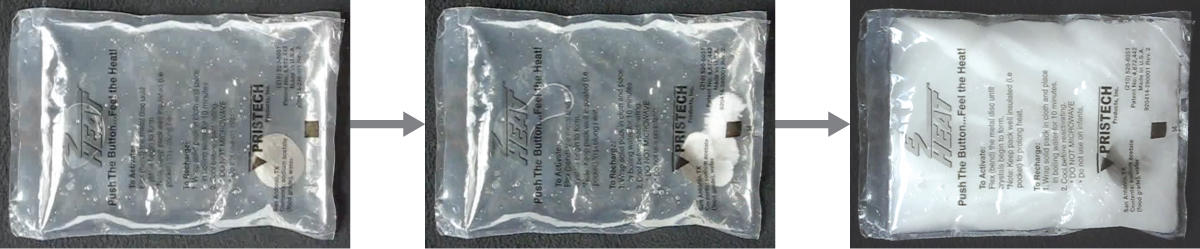

The temperature dependence of solubility can be exploited to prepare supersaturated solutions of certain compounds. A solution may be saturated with the compound at an elevated temperature (where the solute is more soluble) and subsequently cooled to a lower temperature without precipitating the solute. The resultant solution contains solute at a concentration greater than its equilibrium solubility at the lower temperature (i.e., it is supersaturated) and is relatively stable. Precipitation of the excess solute can be initiated by adding a seed crystal or by mechanically agitating the solution. Some hand warmers, such as the one pictured in Figure 10, take advantage of this behavior.

This video shows the crystallization process occurring in a hand warmer.

Surface Tension

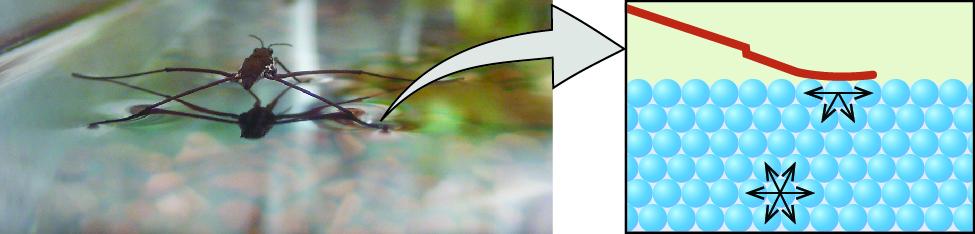

Surface tension is defined as the energy required to increase the surface area of a liquid, or the force required to increase the length of a liquid surface by a given amount. This property results from the cohesive forces between molecules at the surface of a liquid, and it causes the surface of a liquid to behave like a stretched rubber membrane. Surface tensions of several liquids are presented in Table 1. Among common liquids, water exhibits a distinctly high surface tension due to strong hydrogen bonding between its molecules. As a result of this high surface tension, the surface of water represents a relatively “tough skin” that can withstand considerable force without breaking. A steel needle carefully placed on water will float. Some insects, like the one shown in Figure 11, even though they are denser than water, move on its surface because they are supported by the surface tension.

| Substance | Formula | Surface Tension (mN/m) |

| water | H2O | 71.99 |

| mercury | Hg | 458.48 |

| ethanol | C2H5OH | 21.97 |

| octane | C8H18 | 21.14 |

| ethylene glycol | CH2(OH)CH2(OH) | 47.99 |

Demonstration: Surface tension of water

Set up. The following demonstration illustrates the surface tension of water. The high surface tension of water causes sulfur particles to rest on top of water without sinking or mixing.

Explanation. The sulfur particles remain on top of the water until liquid soap is added to the water. Upon addition of liquid soap (a detergent), the cohesive forces between water molecules are disrupted and the sulfur, which is more dense than water, sinks. Another factor in this demonstration is that detergents are amphiphilic, meaning they have both hydrophobic (nonpolar) and hydrophilic (polar) regions. The polar region of the detergent is able to mix with the polar water molecules and the nonpolar region is able to mix with the nonpolar sulfur, thus allowing the sulfur to mix with the water more readily.

Viscosity

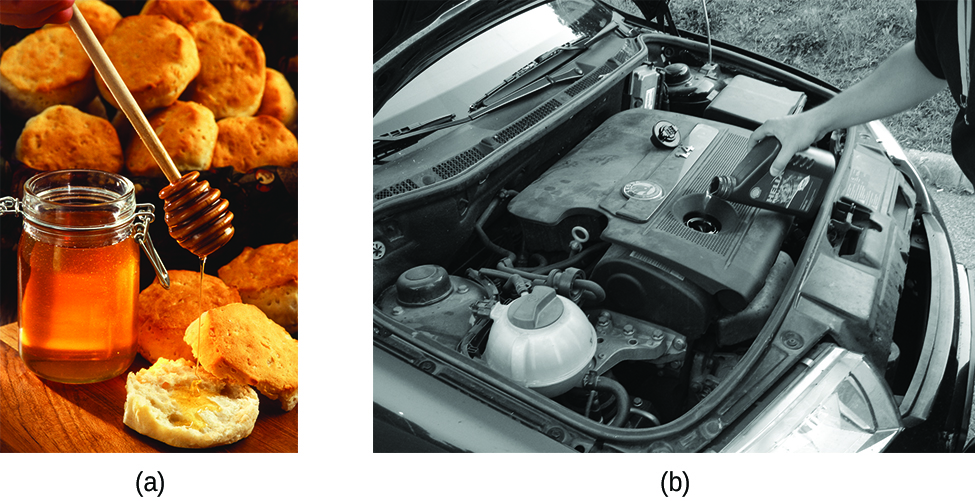

When you pour a glass of water, or fill a car with gasoline, you observe that water and gasoline flow freely. But when you pour syrup on pancakes or add oil to a car engine, you note that syrup and motor oil do not flow as readily. The viscosity of a liquid is a measure of its resistance to flow. Water, gasoline, and other liquids that flow freely have a low viscosity. Honey, syrup, motor oil, and other liquids that do not flow freely, like those shown in Figure 12, have higher viscosities. We can measure viscosity by measuring the rate at which a metal ball falls through a liquid (the ball falls more slowly through a more viscous liquid) or by measuring the rate at which a liquid flows through a narrow tube (more viscous liquids flow more slowly).

The IMFs between the molecules of a liquid, the size and shape of the molecules, and the temperature determine how easily a liquid flows. As Table 2 shows, the more structurally complex the molecules in a liquid are and the stronger the IMFs between them, the more difficult it is for them to move past each other and the greater is the viscosity of the liquid. As the temperature increases, the molecules move more rapidly and their kinetic energies are better able to overcome the forces that hold them together; thus, the viscosity of the liquid decreases.

| Substance | Formula | Viscosity (mPa·s) |

| water | H2O | 0.890 |

| mercury | Hg | 1.526 |

| ethanol | C2H5OH | 1.074 |

| octane | C8H18 | 0.508 |

| ethylene glycol | CH2(OH)CH2(OH) | 16.1 |

| honey | variable | ~2,000–10,000 |

| motor oil | variable | ~50–500 |

Cohesive and Adhesive Forces

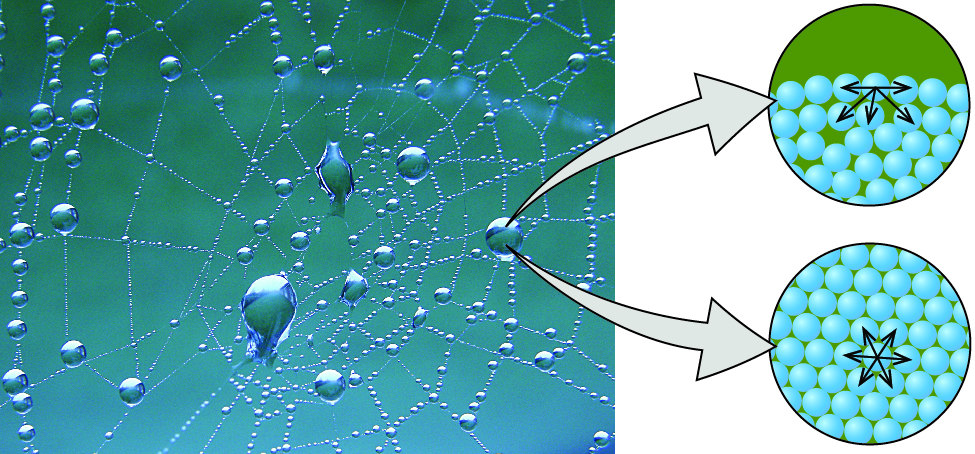

The various IMFs between identical molecules of a substance are examples of cohesive forces. The molecules within a liquid are surrounded by other molecules and are attracted equally in all directions by the cohesive forces within the liquid. However, the molecules on the surface of a liquid are attracted only by about one-half as many molecules. Because of the unbalanced molecular attractions on the surface molecules, liquids contract to form a shape that minimizes the number of molecules on the surface—that is, the shape with the minimum surface area. A small drop of liquid tends to assume a spherical shape, as shown in Figure 13, because in a sphere, the ratio of surface area to volume is at a minimum. Larger drops are more greatly affected by gravity, air resistance, surface interactions, and so on, and as a result, are less spherical.

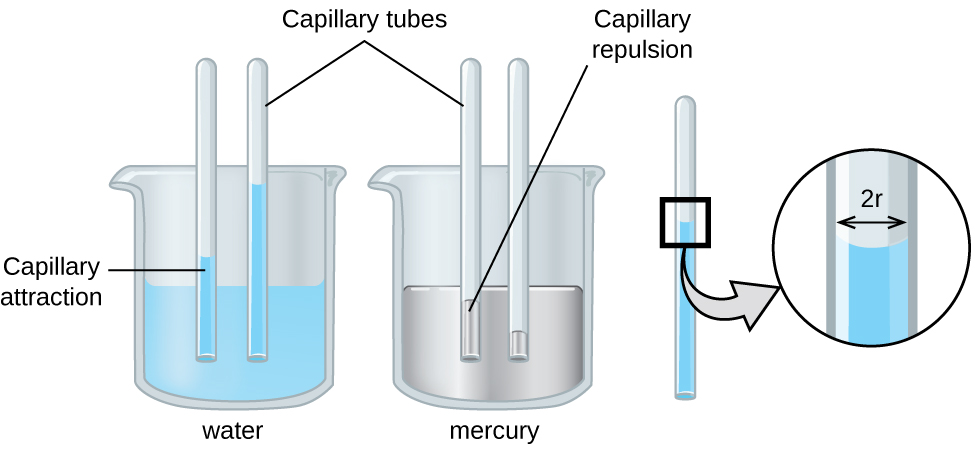

The IMFs of attraction between two different molecules are called adhesive forces. Consider what happens when water comes into contact with some surface. If the adhesive forces between water molecules and the molecules of the surface are weak compared to the cohesive forces between the water molecules, the water does not “wet” the surface. For example, water does not wet waxed surfaces or many plastics such as polyethylene. Water forms drops on these surfaces because the cohesive forces within the drops are greater than the adhesive forces between the water and the plastic. Water spreads out on glass because the adhesive force between water and glass is greater than the cohesive forces within the water. When water is confined in a glass tube, its meniscus (surface) has a concave shape because the water wets the glass and creeps up the side of the tube. On the other hand, the cohesive forces between mercury atoms are much greater than the adhesive forces between mercury and glass. Mercury therefore does not wet glass, and it forms a convex meniscus when confined in a tube because the cohesive forces within the mercury tend to draw it into a drop (Figure 14).

Capillary Forces

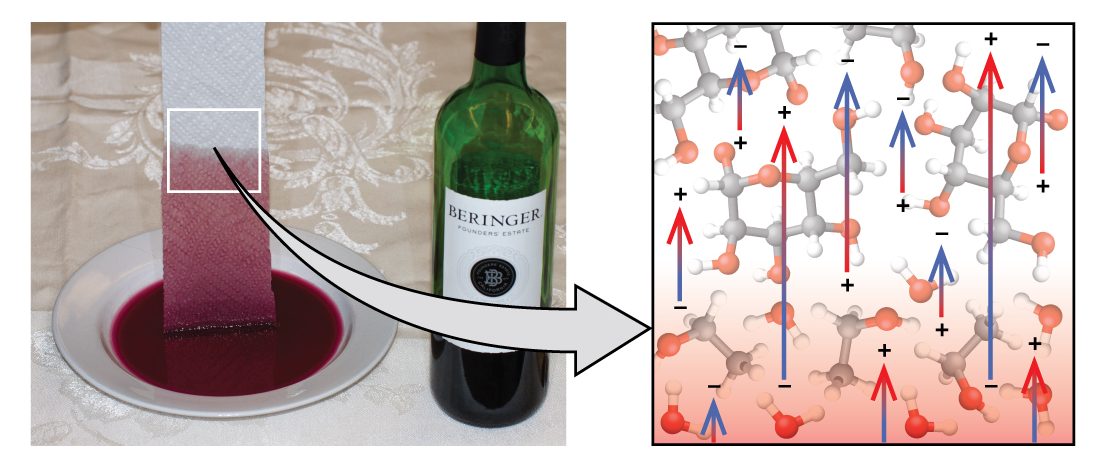

If you place one end of a paper towel in spilled wine, as shown in Figure 15, the liquid wicks up the paper towel. A similar process occurs in a cloth towel when you use it to dry off after a shower. These are examples of capillary action—when a liquid flows within a porous material due to the attraction of the liquid molecules to the surface of the material and to other liquid molecules. The adhesive forces between the liquid and the porous material, combined with the cohesive forces within the liquid, may be strong enough to move the liquid upward against gravity.

Towels soak up liquids like water because the fibers of a towel are made of molecules that are attracted to water molecules. Most cloth towels are made of cotton, and paper towels are generally made from paper pulp. Both consist of long molecules of cellulose that contain many −OH groups. Water molecules are attracted to these −OH groups and form hydrogen bonds with them, which draws the H2O molecules up the cellulose molecules. The water molecules are also attracted to each other, so large amounts of water are drawn up the cellulose fibers.

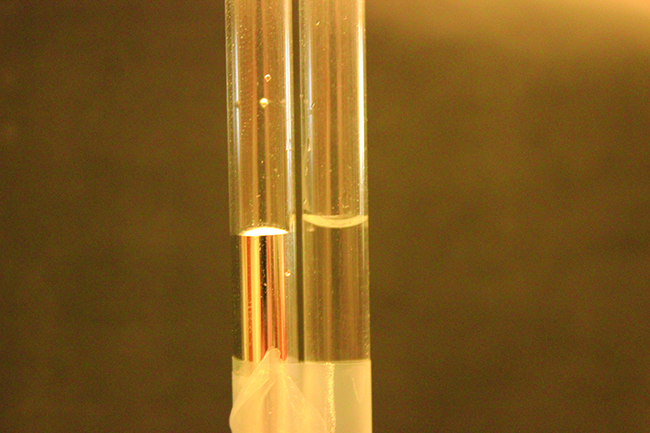

Capillary action can also occur when one end of a small diameter tube is immersed in a liquid, as illustrated in Figure 16. If the liquid molecules are strongly attracted to the tube molecules, the liquid creeps up the inside of the tube until the weight of the liquid and the adhesive forces are in balance. The smaller the diameter of the tube is, the higher the liquid climbs. It is partly by capillary action occurring in plant cells called xylem that water and dissolved nutrients are brought from the soil up through the roots and into a plant. Capillary action is the basis for thin layer chromatography, a laboratory technique commonly used to separate small quantities of mixtures. You depend on a constant supply of tears to keep your eyes lubricated and on capillary action to pump tear fluid away.

Chemistry in Real Life: Biomedical Applications of Capillary Action

Many medical tests require drawing a small amount of blood, such as to determine the amount of glucose in someone with diabetes or the hematocrit level in an athlete. This procedure can be easily done because of capillary action, the ability of a liquid to flow up a small tube against gravity, as shown in Figure 17. When your finger is pricked, a drop of blood forms and holds together due to surface tension—the unbalanced intermolecular attractions at the surface of the drop. Then, when the open end of a narrow-diameter glass tube touches the drop of blood, the adhesive forces between the molecules in the blood and those at the glass surface draw the blood up the tube. How far the blood goes up the tube depends on the diameter of the tube (and the type of fluid). A small tube has a relatively large surface area for a given volume of blood, which results in larger (relative) attractive forces, allowing the blood to be drawn farther up the tube. The liquid itself is held together by its own cohesive forces. When the weight of the liquid in the tube generates a downward force equal to the upward force associated with capillary action, the liquid stops rising.

Key Concepts and Summary

The extent to which one substance will dissolve in another is determined by several factors, including the types and relative strengths of intermolecular attractive forces that may exist between the substances’ atoms, ions, or molecules. Miscible liquids are soluble in all proportions, and immiscible liquids exhibit very low mutual solubility. The viscosity of a substance depends on how easily the molecules can flow past one another in the liquid phase. More complex molecules have more complex interactions, meaning that they will move more slowly and have a higher viscosity. There is some amount of energy required to disturb the surface of a liquid, known as its surface tension. Surface tension arises from the cohesive forces, which are the forces that exist between molecules of the substance. Adhesive forces exist between two different types of molecules. Together, cohesive and adhesive forces are responsible for capillary action — the cohesive forces between the liquid and the adhesive forces between the liquid and the substance through which the liquid travels.

Glossary

- immiscible

- of negligible mutual solubility; typically refers to liquid substances

- miscible

- mutually soluble in all proportions; typically refers to liquid substances

- partially miscible

- of moderate mutual solubility; typically refers to liquid substances

- saturated

- of concentration equal to solubility; containing the maximum concentration of solute possible for a given temperature and pressure

- solubility

- extent to which a solute may be dissolved in water, or any solvent

- supersaturated

- of concentration that exceeds solubility; a nonequilibrium state

- unsaturated

- of concentration less than solubility

Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- Suppose you are presented with a clear solution of sodium thiosulfate, Na2S2O3. How could you determine whether the solution is unsaturated, saturated, or supersaturated?

- Supersaturated solutions of most solids in water are prepared by cooling saturated solutions. Supersaturated solutions of most gases in water are prepared by heating saturated solutions. Explain the reasons for the difference in the two procedures.

- Suggest an explanation for the observations that ethanol, C2H5OH, is completely miscible with water and that ethanethiol, C2H5SH, is soluble only to the extent of 1.5 g per 100 mL of water.

- Calculate the percent by mass of KBr in a saturated solution of KBr in water at 10 °C. See Figure 9 for useful data, and report the computed percentage to one significant digit.

- Which of the following gases is expected to be most soluble in water? Explain your reasoning.

- CH4

- CCl4

- CHCl3

- Refer to Figure 3.

- How did the concentration of dissolved CO2 in the beverage change when the bottle was opened?

- What caused this change?

- Is the beverage unsaturated, saturated, or supersaturated with CO2?

- True or False: Dipole-dipole forces are responsible for sugar dissolving in water.

- True or False: Because Xe is nonpolar, it will not dissolve in water at all.

Answers to Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- If we add a small crystal of sodium thiosulfate in water, it will dissolve in an unsaturated solution, remains unchanged in a saturated solution and starts forming precipitate in a supersaturated solution.

- The solubility of solids usually decreases upon cooling a solution, while the solubility of gases usually decreases upon heating.

- C2H5OH can hydrogen-bond with water while C2H5SH cannot.

- 40%

- C. CHCl3 is a polar molecule, which allows for dipole-dipole interactions with water molecules. The other two choices are both nonpolar molecules.

- (a) The concentration decreases.

(b) The bottle has high pressure when closed. Opening the bottle released CO2 gas and lowered the pressure. The solubility of CO2 decreases with decreasing pressure, therefore, more CO2 gas is released.

(c) Immediately after opening the bottle, the beverage is supersaturated with CO2 because it contains more dissolved CO2 than at equilibrium. - False

- False

Please use this form to report any inconsistencies, errors, or other things you would like to change about this page. We appreciate your comments. 🙂