M7Q7: Electron Configurations, Orbital Box Notation

Introduction

Having introduced the basics of atomic structure and quantum mechanics, we can use our understanding of quantum numbers to determine how atomic orbitals relate to one another. This allows us to determine which orbitals are occupied by electrons in each atom. The specific arrangement of electrons in orbitals of an atom determines many of the chemical properties of that atom. Writing the electron configuration of an element, therefore, provides a useful representation of the electrons occupying the specific orbitals in each atom and suggests the atom’s chemical properties. This section includes worked examples, a glossary, and practice problems.

Learning Objectives for Electron Configurations, Orbital Box Notation:

- Write an electron configuration for an atom.

| Orbital Energies and Electron Configurations of Atoms | - Apply the Aufbau principle to rationalize the structure of the periodic table.

| Aufbau Principle | Writing Orbital Diagrams | Electron Configuration Exceptions |

| Key Concepts and Summary | Glossary | End of Section Exercises |

Orbital Energies and Electron Configurations of Atoms

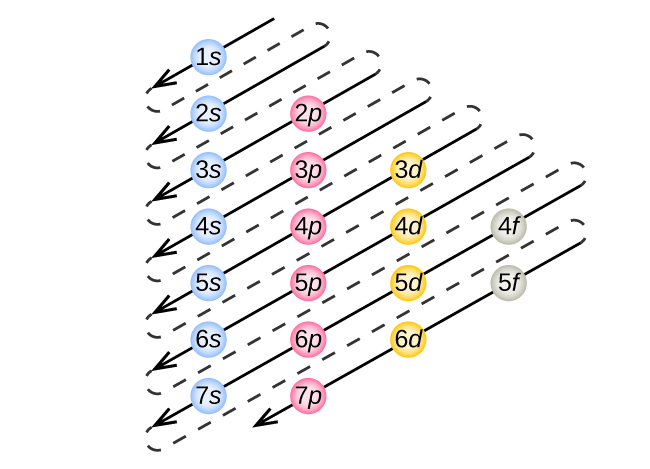

The energy of atomic orbitals increases as the principal quantum number, n, increases. In any atom with two or more electrons, the repulsion between the electrons makes energies of subshells with different values of l differ so that the energy of the orbitals increases within a shell in the order s < p < d < f. Figure 1 depicts the trends of increasing energy with increasing n and increasing l (note that this is different than the orbital diagram that we saw in the previous section for hydrogen because now we have more than one electron). The 1s orbital at the bottom of the diagram is the orbital with electrons of lowest energy. The energy increases as we move up to the 2s and then 2p, 3s, and 3p orbitals, showing that the increasing n value has more influence on energy than the increasing l value for small atoms. However, this pattern does not hold for larger atoms. For example, the 3d orbital is higher in energy than the 4s orbital. Such overlaps continue to occur frequently as we move up the chart.

Electrons in successive atoms on the periodic table tend to fill low-energy orbitals first. Thus, many students find it confusing that, for example, the 5p orbitals fill immediately after the 4d, and immediately before the 6s. The filling order is based on observed experimental results, and has been confirmed by theoretical calculations. As the principal quantum number, n, increases, the size of the orbital increases and the electrons spend more time farther from the nucleus. Thus, the attraction to the nucleus is weaker and the energy associated with the orbital is higher (less stabilized). But this is not the only effect we have to take into account. Within each shell, as the value of l increases, the electrons are less penetrating (meaning there is less electron density found close to the nucleus), in the order s > p > d > f. Electrons that are closer to the nucleus slightly repel electrons that are farther out, offsetting the more dominant electron–nucleus attractions slightly (recall that all electrons have −1 charges, but nuclei have +Z charges). This phenomenon is called shielding and will be discussed in more detail in the next section. Electrons in orbitals that experience more shielding are less stabilized and thus higher in energy. For small orbitals (1s through 3p), the increase in energy due to n is more significant than the increase due to l; however, for larger orbitals the two trends are comparable and cannot be simply predicted.

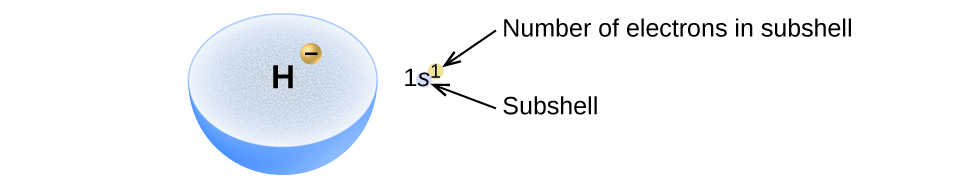

The arrangement of electrons in the orbitals of an atom is called the electron configuration of the atom. We describe an electron configuration with a symbol that contains three pieces of information (Figure 2):

- The number of the principal quantum number, n,

- The letter that designates the orbital type (the subshell, l), and

- A superscript number that designates the number of electrons in that particular subshell.

For example, 2p4 indicates four electrons in a p subshell (l = 1) with a principal quantum number (n) of 2. The notation 3d8 (read “three–d–eight”) indicates eight electrons in the d subshell (l = 2) of the principal shell for which n = 3.

The Aufbau Principle

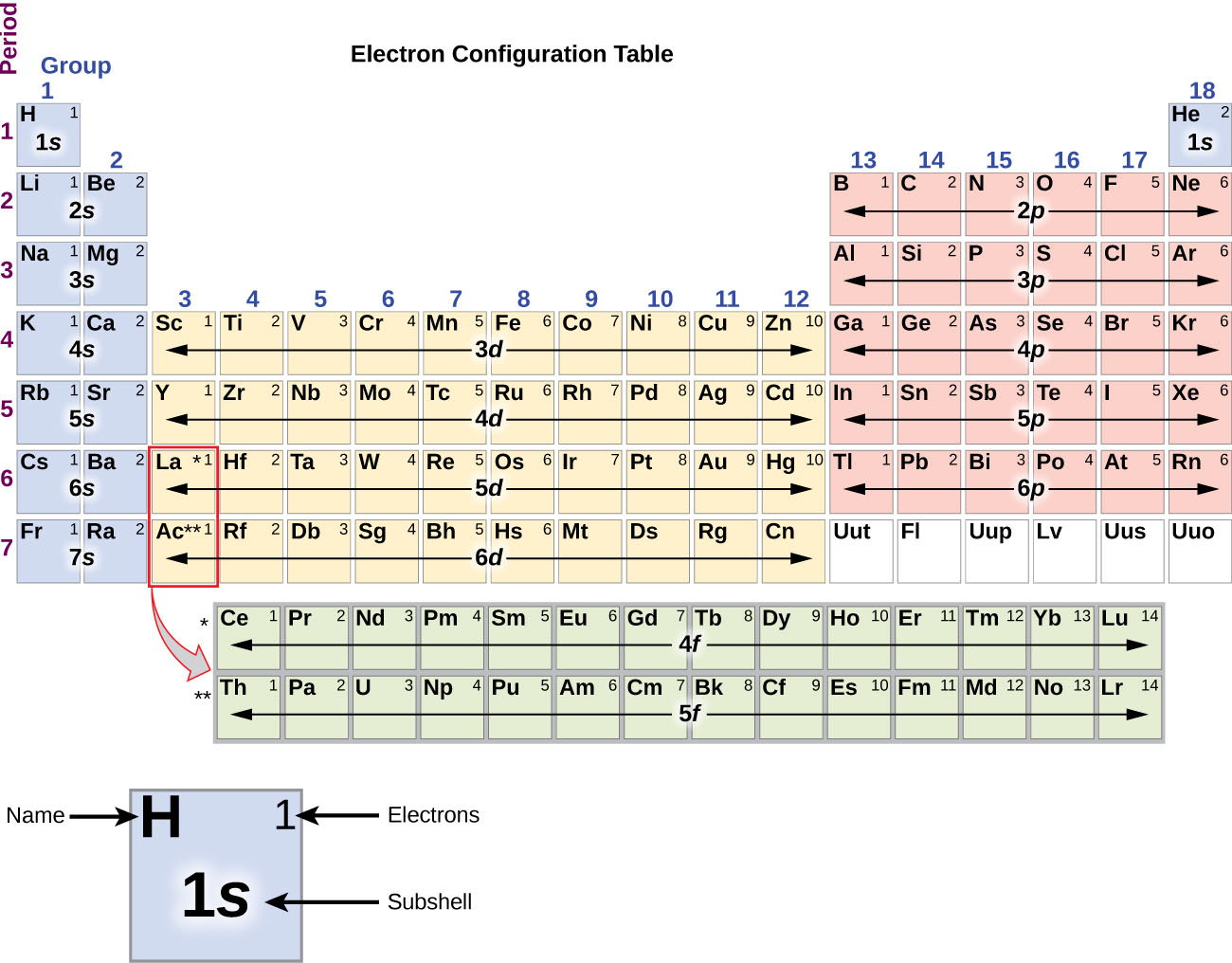

To determine the electron configuration for any particular atom, we can “build” the structures in the order of atomic numbers. Beginning with hydrogen, and continuing across the periods of the periodic table, we add one proton at a time to the nucleus and one electron to the proper subshell until we have described the electron configurations of all the elements. This procedure is called the Aufbau principle, from the German word Aufbau (“to build up”). Each added electron occupies the subshell of lowest energy available (in the order shown in Figure 1), subject to the limitations imposed by the allowed quantum numbers according to the Pauli exclusion principle. Electrons enter higher-energy subshells only after lower-energy subshells have been filled to capacity. Figure 3 illustrates the traditional way to remember the filling order for atomic orbitals. Since the arrangement of the periodic table is based on the electron configurations, Figure 4 provides an alternative method for determining the electron configuration. The filling order simply begins at hydrogen and includes each subshell as you proceed in increasing Z order. For example, after filling the 3p block up to Ar, we see the orbital will be 4s (K, Ca), followed by the 3d orbitals.

Writing Orbital Diagrams

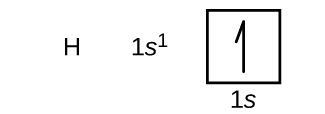

We will now construct the ground-state electron configuration and orbital diagram for a selection of atoms in the first and second periods of the periodic table. Orbital diagrams are pictorial representations of the electron configuration, showing the individual orbitals and the pairing arrangement of electrons. We start with a single hydrogen atom (atomic number 1), which consists of one proton and one electron. Referring to Figure 3 or Figure 4, we would expect to find the electron in the 1s orbital. By convention, the ms = +½ value is usually filled first. The electron configuration and the orbital diagram are:

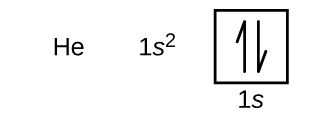

Following hydrogen is the noble gas helium, which has an atomic number of 2. The helium atom contains two protons and two electrons. The first electron has the same four quantum numbers as the hydrogen atom electron (n = 1, l = 0, ml = 0, ms = +½). The second electron also goes into the 1s orbital and fills that orbital. The second electron has the same n, l, and ml quantum numbers, but must have the opposite spin quantum number, ms = -½. This is in accord with the Pauli exclusion principle: No two electrons in the same atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers. For orbital diagrams, this means two arrows go in each box (representing two electrons in each orbital) and the arrows must point in opposite directions (representing paired spins). The electron configuration and orbital diagram of helium are:

The n = 1 shell is completely filled in a helium atom.

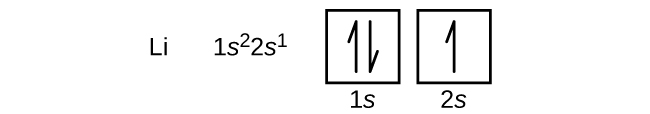

The next atom is the alkali metal lithium with an atomic number of 3. The first two electrons in lithium fill the 1s orbital and have the same sets of four quantum numbers as the two electrons in helium. The remaining electron must occupy the orbital of next lowest energy, the 2s orbital (Figure 3 or Figure 4). Thus, the electron configuration and orbital diagram of lithium are:

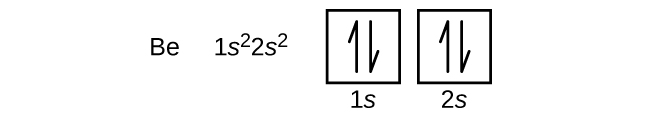

An atom of the alkaline earth metal beryllium, with an atomic number of 4, contains four protons in the nucleus and four electrons surrounding the nucleus. The fourth electron fills the remaining space in the 2s orbital.

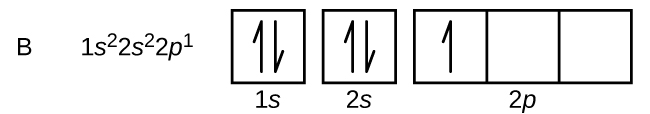

An atom of boron (atomic number 5) contains five electrons. The n = 1 shell is filled with two electrons and three electrons will occupy the n = 2 shell. Because any s subshell can contain only two electrons, the fifth electron must occupy the next energy level, which will be a 2p orbital. There are three degenerate 2p orbitals (ml = −1, 0, +1) and the electron can occupy any one of these p orbitals. When drawing orbital diagrams, we include empty boxes to depict any empty orbitals in the same subshell that we are filling.

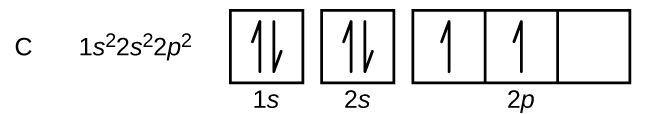

Carbon (atomic number 6) has six electrons. Four of them fill the 1s and 2s orbitals. The remaining two electrons occupy the 2p subshell. We now have a choice of filling one of the 2p orbitals and pairing the electrons or of leaving the electrons unpaired in two different, but degenerate, p orbitals. The orbitals are filled as described by Hund’s rule: The lowest-energy configuration for an atom with electrons within a set of degenerate orbitals is that having the maximum number of unpaired electrons with parallel spins. Placing the electrons in different orbitals and with parallel spins tends to keep the electrons in different regions of space, thus minimizing their Coulomb repulsion and lowering the energy. Thus, the two electrons in the carbon 2p orbitals have identical n, l, and ms quantum numbers and differ in their ml quantum number (in accord with the Pauli exclusion principle). The electron configuration and orbital diagram for carbon are:

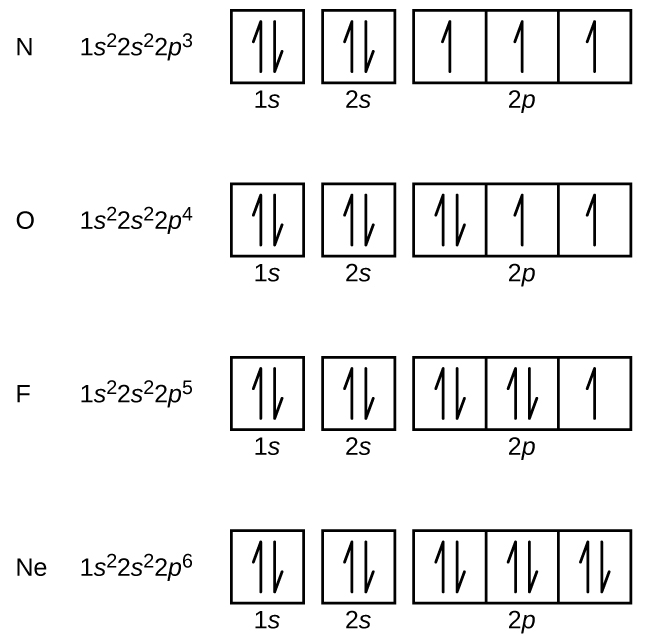

Nitrogen (atomic number 7) fills the 1s and 2s subshells and has one electron in each of the three 2p orbitals, in accordance with Hund’s rule. These three electrons have unpaired spins. Oxygen (atomic number 8) has a pair of electrons in any one of the 2p orbitals (the electrons have opposite spins) and a single electron in each of the other two. Fluorine (atomic number 9) has only one 2p orbital containing an unpaired electron. All of the electrons in the noble gas neon (atomic number 10) are paired, and all of the orbitals in the n = 1 and the n = 2 shells are filled. The electron configurations and orbital diagrams of these four elements are:

The alkali metal sodium (atomic number 11) has one more electron than the neon atom. This electron must go into the lowest-energy subshell available, the 3s orbital, giving a 1s22s22p63s1 configuration. We can abbreviate electron configurations by writing the a noble gas configuration, which consists of the elemental symbol of the last noble gas prior to that atom, followed by the configuration of the remaining electrons. For our sodium example, the noble gas (or abbreviated or condensed) configuration is [Ne]3s1.

When we come to the alkali metal potassium (atomic number 19), we might expect that we would begin to add electrons to the 3d subshell. However, all available chemical and physical evidence indicates that potassium is like lithium and sodium, and that the next electron is not added to the 3d level but is, instead, added to the 4s level. As discussed previously, the 3d orbital with no radial nodes is higher in energy because it is less penetrating and more shielded from the nucleus than the 4s, which has three radial nodes. Thus, potassium has an electron configuration of [Ar]4s1.

Beginning with the transition metal scandium (atomic number 21), additional electrons are added successively to the 3d subshell. This subshell is filled to its capacity with 10 electrons (remember that for l = 2 [d orbitals], there are 2l + 1 = 5 values of ml, meaning that there are five d orbitals that have a combined capacity of 10 electrons). The 4p subshell fills next. Note that for three series of elements, scandium (Sc) through copper (Cu), yttrium (Y) through silver (Ag), and lutetium (Lu) through gold (Au), a total of 10 d electrons are successively added to the (n – 1) shell next to the n shell to bring that (n – 1) shell from 8 to 18 electrons. For two series, lanthanum (La) through lutetium (Lu) and actinium (Ac) through lawrencium (Lr), 14 f electrons (l = 3, 2l + 1 = 7 ml values; thus, seven orbitals with a combined capacity of 14 electrons) are successively added to the (n – 2) shell to bring that shell from 18 electrons to a total of 32 electrons.

Example 1

Quantum Numbers and Electron Configurations

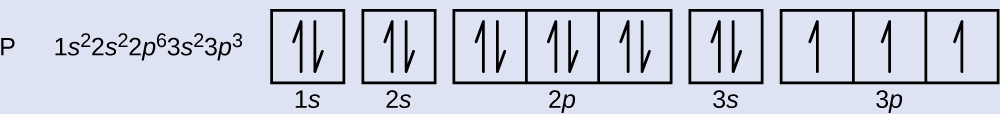

What is the electron configuration and orbital diagram for a phosphorus atom? What are the four quantum numbers for the last electron added?

Solution

The atomic number of phosphorus is 15. Thus, a phosphorus atom contains 15 electrons. The order of filling of the energy levels is 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, . . . The 15 electrons of the phosphorus atom will fill up to the 3p orbital, which will contain three electrons:

The last electron added is a 3p electron. Therefore, n = 3 and, for a p-type orbital, l = 1. The ml value could be –1, 0, or +1. The three p orbitals are degenerate, so any of these ml values is correct. For unpaired electrons, convention assigns the value of +½ for the spin quantum number; thus, ms = +½.

Check Your Learning

Identify the atoms from the electron configurations given:

- [Ar]4s23d5

- [Kr]5s24d105p6

Answer:

(a) Mn; (b) Xe

Electron Configuration Exceptions

The periodic table can be a powerful tool in predicting the electron configuration of an element. However, we do find exceptions to the order of filling of orbitals shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4. For instance, the ground state electron configuration of the transition metal chromium (Cr; atomic number 24) is [Ar]4s13d5 and that of copper (Cu; atomic number 29) is [Ar]4s13d10. In general, such exceptions involve subshells with very similar energy, and small effects can lead to changes in the order of filling.

In the case of Cr and Cu, we find that half-filled and completely filled subshells apparently represent conditions of preferred stability. This stability is such that an electron shifts from the 4s into the 3d orbital to gain the extra stability of a half-filled 3d subshell (in Cr) or a filled 3d subshell (in Cu). Other exceptions also occur. For example, niobium (Nb, atomic number 41) is predicted to have the electron configuration [Kr]5s24d3. Experimentally, we observe that its ground-state electron configuration is actually [Kr]5s14d4. We can rationalize this observation by saying that the electron–electron repulsions experienced by pairing the electrons in the 5s orbital are larger than the gap in energy between the 5s and 4d orbitals. There is no simple method to predict the exceptions for atoms where the magnitude of the repulsions between electrons is greater than the small differences in energy between subshells.

Key Concepts and Summary

The relative energy of the subshells determine the order in which atomic orbitals are filled (1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, and so on). Electron configurations and orbital diagrams can be determined by applying the Pauli exclusion principle (no two electrons can have the same set of four quantum numbers) and Hund’s rule (whenever possible, electrons retain unpaired spins in degenerate orbitals).

Glossary

- Aufbau principle

- procedure in which the electron configuration of the elements is determined by “building” them in order of atomic numbers, adding one proton to the nucleus and one electron to the proper subshell at a time

- electron configuration

- electronic structure of an atom in its ground state given as a listing of the orbitals occupied by the electrons

- Hund’s rule

- every orbital in a subshell is singly occupied with one electron before any one orbital is doubly occupied, and all electrons in singly occupied orbitals have the same spin

- orbital diagram

- pictorial representation of the electron configuration showing each orbital as a box and each electron as an arrow

Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- Using complete subshell notation (1s22s22p6, and so forth), predict the electron configuration of each of the following atoms:

- N

- Si

- Fe

- Te

- Tb

- Is 1s22s22p6 the symbol for a macroscopic property or a microscopic property of an element? Explain your answer.

- Which atom has the electron configuration 1s22s22p63s23p64s23d104p65s24d2?

- Cobalt–60 and iodine–131 are radioactive isotopes commonly used in nuclear medicine. How many protons, neutrons, and electrons are in atoms of these isotopes? Write the complete electron configuration for each isotope.

- Which atom would be expected to have a half-filled 4s subshell?

- Which atom would be expected to have a half-filled 6p subshell?

- Which of the following has two unpaired electrons?

- Mg

- Si

- S

- Both Mg and S

- Both Si and S

- Write a set of quantum numbers for each of the electrons with an n of 3 in a Sc atom.

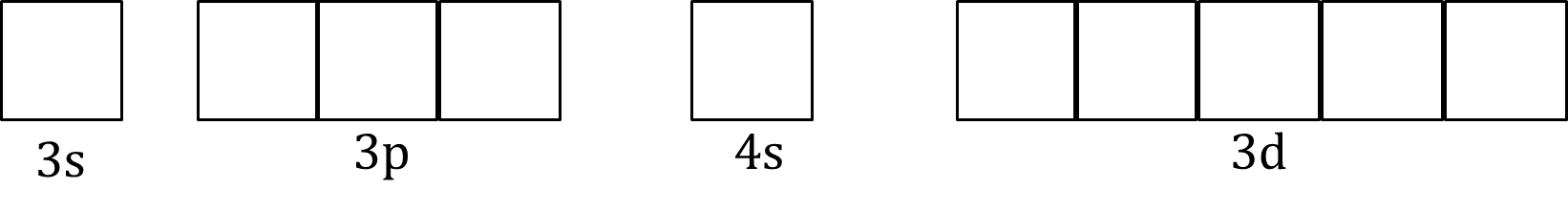

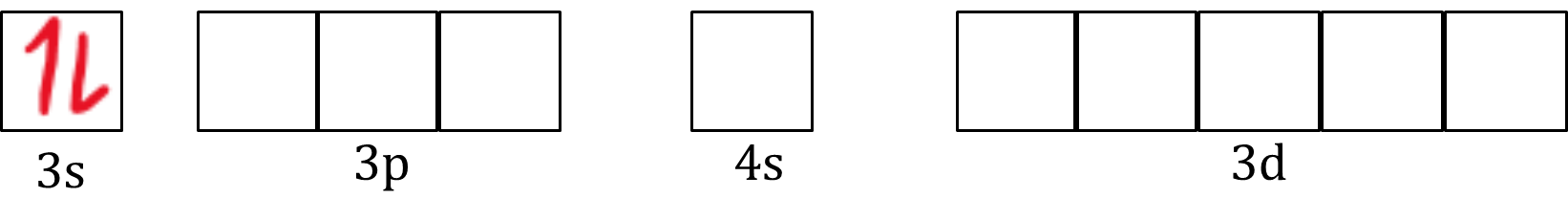

- Fill in the box diagrams below to give ground state electron configurations for Mg and V.

[Ne]

Answers to Chemistry End of Section Exercises

- (a) 1s22s22p3

(b) 1s22s22p63s23p2

(c) 1s22s22p63s23p64s23d6

(d) 1s22s22p63s23p64s23d104p65s24d105p4

(e) 1s22s22p63s23p64s23d104p65s24d105p66s24f9 - Microscopic property. We cannot see shells, subshells, and orbitals with our eyes, and they describe very specific qualities of electrons in an atom

- Zr

- Co-60 has 27 protons, 27 electrons, and 33 neutrons: 1s22s22p63s23p64s23d7. I-131 has 53 protons, 53 electrons, and 78 neutrons: 1s22s22p63s23p63d104s24p64d105s25p5.

- K

- Bi

- Although both B and C are correct, E encompasses both and is the best answer.

-

n l ml ms 3 0 0 +½ 3 0 0 -½ 3 1 -1 +½ 3 1 -1 -½ 3 1 0 +½ 3 1 0 -½ 3 1 1 +½ 3 1 1 -½ 3 2 -2 +½ - Mg: [Ne]

V: [Ne]

Please use this form to report any inconsistencies, errors, or other things you would like to change about this page. We appreciate your comments. 🙂