D16.3 Proteins

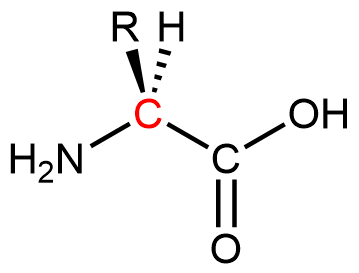

Proteins are condensation polymers made from amino acids. An amino acid consists of a carbon atom (called the α carbon, shown in red below) bonded to a hydrogen atom, an amine group, a carboxylic acid group, and an R group, often called the side chain .

Notice that the α carbon is chiral when the “R” group differs from the other three groups. About 500 naturally occurring amino acids are known, although only twenty are found in protein molecules in humans. Of these twenty amino acids, nineteen have a chiral α carbon.

Exercise 1: Features of Amino-Acid Molecules

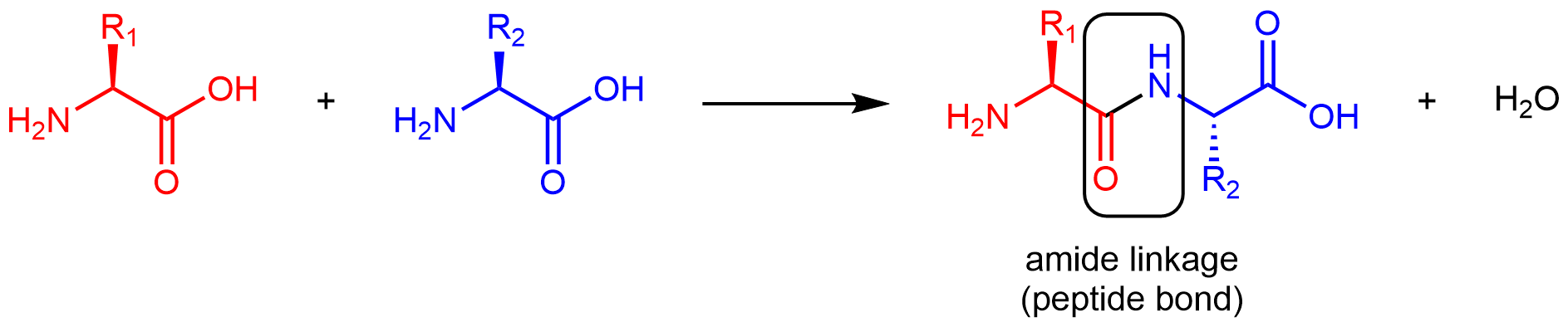

Amino acids are linked together in proteins by amide linkages formed via condensation reactions. An amide linkage in a protein is often called a peptide bond.

Note that the reaction does not involve the α carbon atom, and the chirality at the α carbon remains the same after the reaction. (In the product molecule above, R2 is depicted with a dashed bond because the amino acid shown in blue has been rotated 180° around a horizontal axis from the reactant to the product.)

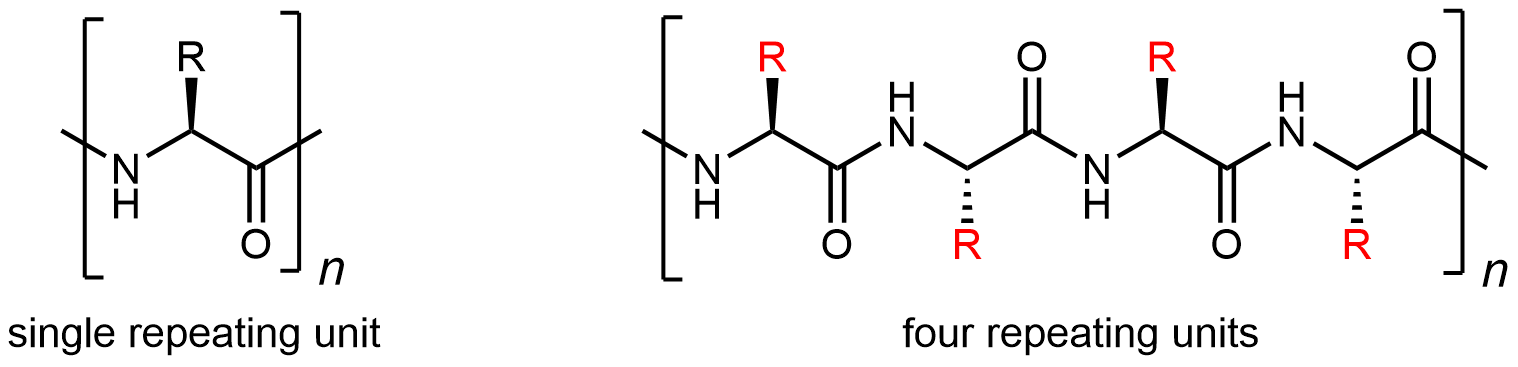

Like all amide functional groups, the amide linkages in a protein strand are planar. The α carbon atoms, however, have tetrahedral local geometry. This molecular chain of α carbons connected by amide groups, is referred to as the protein backbone. It is the main chain of a strand of protein. The amino acid R groups are called side chains because they are attached to, but branch off from, the main chain.

Protein molecules are complicated: there are 20 different kinds of monomers that can be linked to form a huge number of different polymer chains. Thus protein structures are classified in several ways.

Fundamental is the sequence in which the amino acids are linked: the primary structure. Because there are 20 possibilities for each side chain (highlighted in red below), there is a vast number of different protein primary structures possible.

Segments of a long protein strand can adopt unique three-dimensional secondary structures. The type of secondary structure is defined by the pattern of hydrogen bonds between non-adjacent backbone amide groups. Two common elements of secondary structure are present in over 60% of known proteins. One is the α-helix, which has a regular pattern of hydrogen bonding between backbone amide groups.

For the segment shown above, the C=O of amino acid 1 forms a hydrogen bond with N-H of amino acid 5; the C=O of amino acid 2 forms a hydrogen bond with N-H of amino acid 6; etc. This regularly repeating hydrogen bonding is a prominent characteristic of an α-helix.

The other type of secondary structure is the β-sheet, which consists of stretches of the protein chain connected side-by-side by hydrogen bonds between backbone amide groups. This gives rise to a general pleated sheet appearance, rotate figure below for a side view.

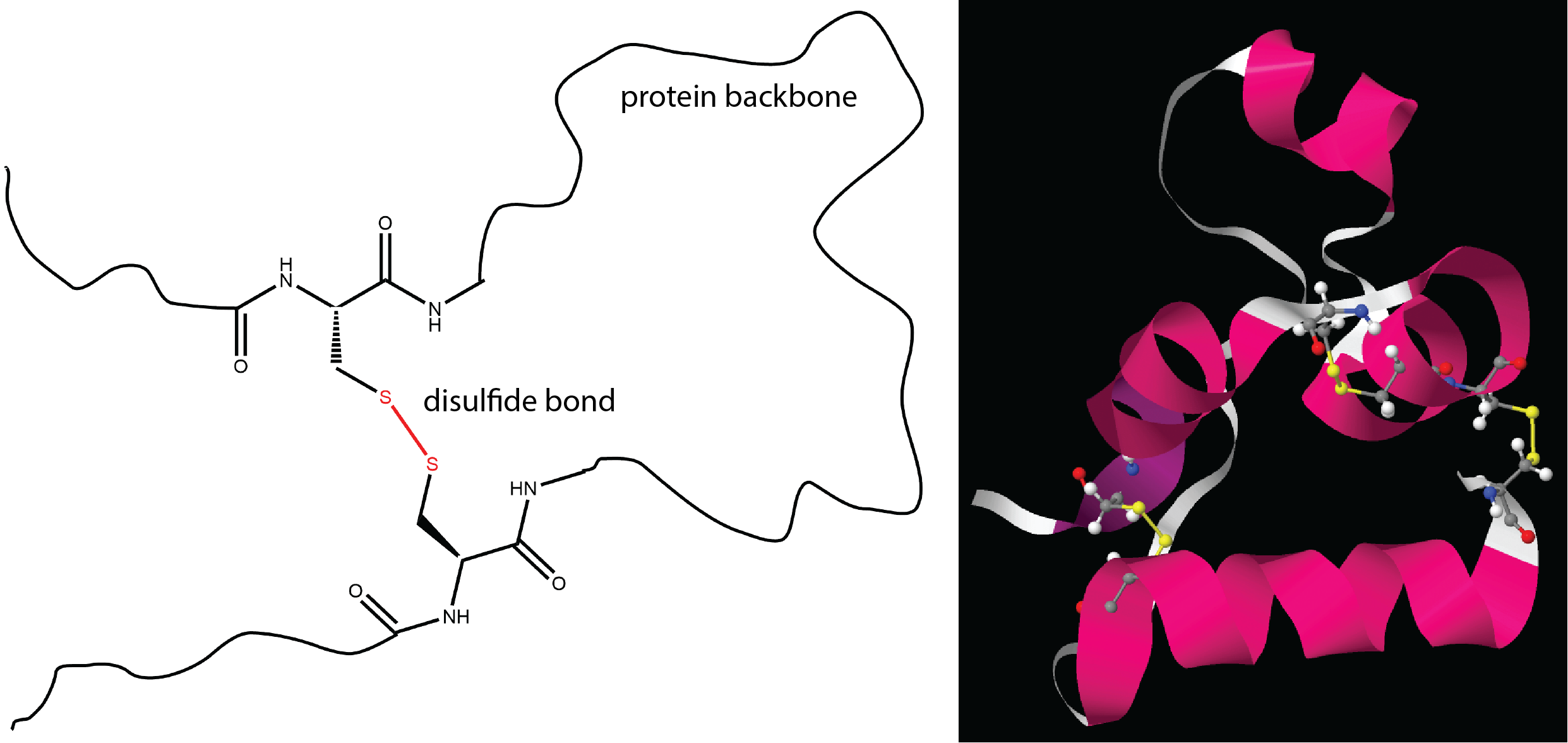

The tertiary structure of a protein is the overall three-dimensional shape of the protein. They are often defined by various intermolecular interactions involving the protein’s side-chains as well as the environment the protein is in.

One important determinant of tertiary structure in some proteins is the disulfide bond. It is similar to the cross-linking we discussed for addition polymers.

The unique three-dimensional secondary and tertiary structures of each protein are dependent on its primary structure. When two or more strands of proteins are held together by intermolecular forces, they can also adopt specific quaternary structures. For example, the hemoglobin in your blood is composed of four chains (colored peach, blue, green, and yellow).

Please use this form to report any inconsistencies, errors, or other things you would like to change about this page. We appreciate your comments. 🙂