Arabic – Modern Standard Arabic (MSA)

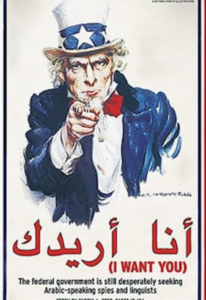

Arabic: A “Less Commonly Taught” and/or a “Critical” Language?

Arabic is currently the eighth most studied language in the United States. At the United Nations, Arabic is one of only two non-European languages with official status. So, why is it categorized as a “less commonly taught language?”

The interest in studying Arabic in the United States boomed after September 11th, 2001. It was no accident that this boom coincided with huge streams of federal funding dedicated to promoting its study among American citizens, especially via study abroad programs. For instance, during the 2000-2001 academic year, 890 students from U.S. institutions of higher education studied for academic credit in the Middle East and North Africa region. This jumped dramatically twelve years later with approximately 6,415 students from U.S. institutions of higher education studying in the region for academic credit

So, this begs the question: Is Arabic a “less commonly taught language”? What is a “less commonly taught language”? How has Arabic’s position as a “critical” language since September 11th shaped the way the language is taught in and outside of the United States? What is the difference between a “critical language” and a “less commonly taught language”? How have the uprisings and revolutions in the Middle East and North Africa since 2011 shaped Arabic language curriculum and programs in the region?

Timeline of broad investments on the relationship between language instruction and geopolitics in the United States since the 1950s

- Linguistic knowledge and World War II: Linkages between military, government and academic institutions were solidified during World War II with the strategic need for area studies knowledge.

- Sputnik (1957) and the Cold War spurred further investment in area studies/ language and higher education. During this time various federal-academic partnerships were established via the National Defense Education Act, which was run by the Department of Education

- After the end of the Cold War, these investments started to decline.

- “9/11 was our Sputnik:” With September 11th, there was an increasing interest in language education once again, with the emergence of the category “critical” languages. These languages have changed over time, but include languages such as Russian, Arabic, Mandarin, Pashto, Farsi, Swahili and Urdu.

- After 9/11, the National Security Language Initiative was established and run by Department of Defense, State, and Education. The shift here being that this language initiative (unlike ones established during WWII and the Cold War) was not just run by the Department of Education. With the National Language Flagship Initiative, there was a proliferation of funding and programs for the study of critical languages.

Geopolitics and Arabic Language Education: how are these shifts are felt in classrooms?

- After 2001, there were huge increases in students studying abroad, primarily concentrated in Egypt and Morocco.

- However after the revolutions and uprisings in the region since 2011, there has been a massive shift in the geography of Arabic language education for American study abroad students in the region.

- Since 2011, more students are studying in Jordan than Egypt.

- Funding streams and geopolitics has shaped Arabic curricular focus and pedagogy, especially for study abroad students, undergraduates, and graduate students coming from U.S. institutions.

- For example, at the American University in Cairo (2009-2010) curriculum was geared to U.S. government exams and language proficiency. There was a primary focus on media vocabulary and structures, rather than grammar. Vocabulary was oriented around current events, particularly terrorism and the War on Terror

- Since 2011, there has been a shift to programs in Amman, Jordan and topics of humanitarianism and refugees. Media classes are also focused on current events; however, there is a primary focus on citizenship, human rights, and humanitarianism.

If you are a recipient of language funding from the U.S. Department of Education or other U.S. government funding to study in the Middle East and North Africa, your studies will inevitably be shaped by these streams of funding. Where are you studying and why? What themes is your program focusing on? What vocabulary are you learning? How is dialect being incorporated into your studies? These are all critical questions to ask wherever you are studying, but especially important if you have funding or institutional support that channels you to specific spaces and programs.

Feel free to share your experiences below and general thoughts on the shifting political economy of Arabic language education!

For further insight the relationship between geopolitics and Arabic:

- Hawker, Nancy. 2016 “Arabic for Spies,” New Left Review, 102, Nov/Dec 2016.

- Institute of International Education “Host Regions and Destinations of U.S. Study Abroad Students, 2000/01-2013-2014” Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange.

- Newhall, Amy. 2006.“The Unraveling of the Devil’s Bargain: The History and Politics of Language Acquisition” in Academic Freedom after September 11, edited by Beshara Doumani, Zone Books.

- Stone, Chris. 2014. “Teaching Arabic in the US after 9/11” in Jadaliyya